In 2016–the same year that Limbo follow-up Inside released to critical acclaim–two of the developers behind Playdead’s latest puzzle platformer made a big announcement: They were leaving the company.

Following their work on Inside, lead gameplay designer Jeppe Carlsen and programmer/composer Jakob Schmid decided it was time to forge a new identity and, with it, a new studio. The pair founded Geometric Interactive later that year and began work on Cocoon, an ambitious puzzle game that would be “structurally and fundamentally different” from any game they had worked on before–and, as Carlsen told GameSpot in an exclusive interview, was simply “too fascinating to not do it.”

“Initially it was just all these thought experiments about exploring a hierarchy of worlds and how you could manipulate the hierarchy in different interesting ways to build puzzles that had a new way of thinking and a freshness to it,” Carlsen said. “Everything started with just that mechanical idea … And every time I thought about it, I was just even more set in stone about, ‘This game has to be made. It’s too fascinating to not do it.'”

According to Carlsen, Cocoon was the seed from which Geometric Interactive grew. But though we know now that the result of this endeavor would be a rousing success, the transition from working within a studio to creating one of their own required a fair bit of personal puzzle-solving.

“It was very scary in the beginning,” Schmid told GameSpot. “It was a lot to deal with.”

Schmid added that, as a founder, a lot of responsibilities (more specifically those pertaining to the game’s audio, music, and sound) ultimately fell upon him until the pair brought in additional developers. However, Carlsen explained how, in many ways, that responsibility was something he had been longing for.

“When I left Playdead, the company had grown to a certain size. And when a company is a certain size, there are–for most things you’ll sit down and do–there’ll be someone better than you at doing it,” Carlsen said. “I’m a decent programmer. I’m not the best programmer in the world, but I do enjoy programming. Starting over is just the sort of variation [I needed] that I maybe missed a little bit.”

In addition to enabling Carlsen to revisit his love of programming, creating Geometric Interactive, and subsequently Cocoon, also allowed him to explore a new identity–one rooted in computer science, geometry, logic, and mathematics above all else. As such, Cocoon was designed perhaps a bit differently than you might imagine. Carlsen revealed that the game’s plot, tone, and setting were all “up in the air” when the team began working on it. Instead, they “focused on a more mathematical game design kind of idea.” Yet, and as any game developer will tell you, envisioning a game and creating one are two different beasts entirely.

“There’s always this little bit of anxious transition when you actually start building the game because then you see all the problems. But I think most of it was in those very first steps [and] it was a positive surprise that it made sense,” Carlsen said. “Then of course there’s a lot of unseen challenges and stuff that you don’t fully simulate [in your imagination], especially for Cocoon. I think it’s a structural challenge. The biggest game design problem has been, ‘How do I structure this so it’s well paced and it’s always accessible?'”

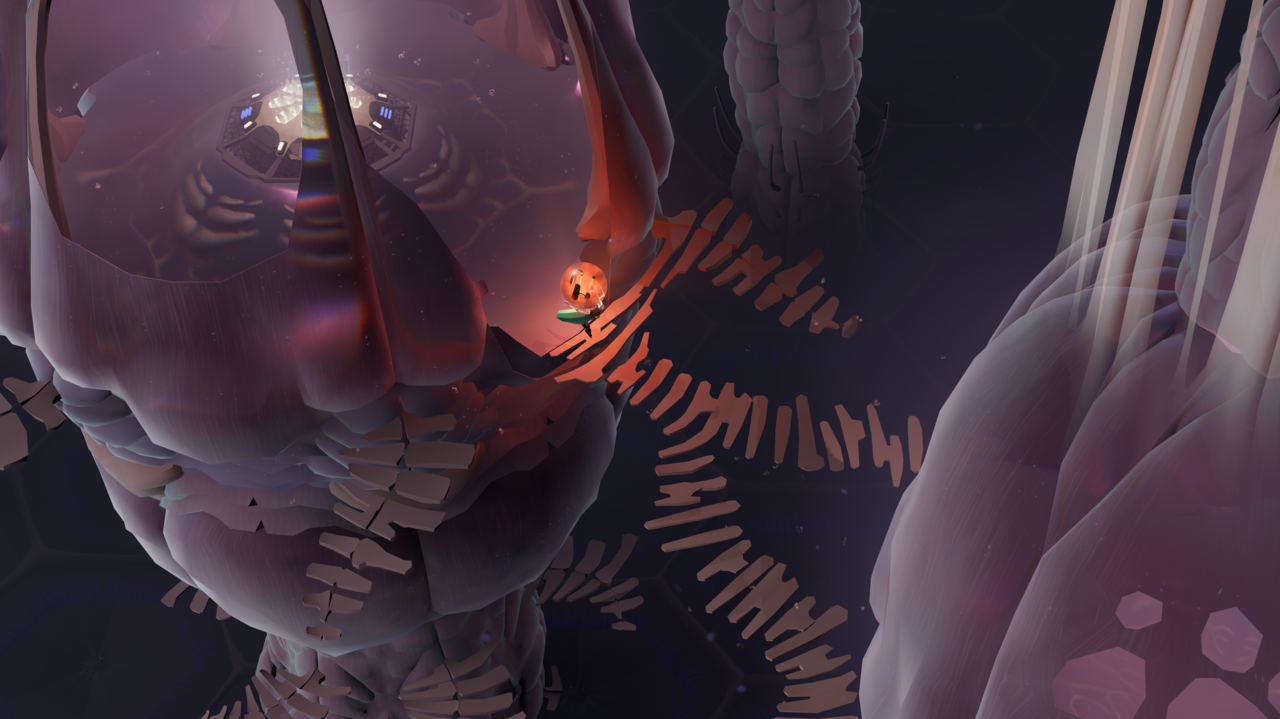

It’s easy to see just how Cocoon would present structural challenges. In it, you play as a beetle-like insect that traverses unique biomes in search of orbs containing entire worlds. You can then place these orbs into mechanisms that project them in a puddle on the ground, which you can seamlessly enter. However, while carrying a particular orb, you also attain a distinct power that is then lost as soon as you set it down. The game then becomes an elaborate puzzle, as you shuffle around orbs and work within the game’s unique logic to progress.

To help combat this complexity and add structure, Carlsen came to the conclusion that certain aspects of the game should remain simple. In particular, the team settled on the idea that Cocoon would be a linear experience with simple mechanics: four directional keys to move, and a single button to interact.

“From a very, very early point, I was aware that this is probably in some aspects the most complex game idea that I’ve ever worked on. And it just feels natural for me that the more complex something is, the more you also have to pull it in the other direction and sort of simplify it to not scare people away,” Carlsen said.

“It [also] gives me control, as a puzzle designer, to communicate more clearly to the player when they need to shoot and sort of lay out the puzzles,” Carlsen continued. “For example, when I need to teach you something new, how can I make sure that… if I need to teach you something about the purple orb, that the orange and the green orb [are] not adding noise to the learning experience?”

Even so, Carlsen said that a lot of locations and some puzzles were changed in late production to prevent confusion. While narrowing down the area players could explore prevented a lot of frustrating backtracking, Cocoon’s linearity introduced its own set of problems that were revealed through Geometric Interactive’s extensive playtesting: If players didn’t understand exactly what Carlsen wanted them to understand, the game “comes to a halt.” Fortunately, this is where Jakob Schmid’s auditory expertise came into play.

“Jeppe came up with this idea of whenever the player has expanded their mind, it’s like you have learned, ‘Oh, this is a thing you can do in this game that’s really, really important,” Schid said. “And [I had] generated these little tones that had this kind of beautiful quality to [them]. So I was just like, ‘Yes, I haven’t found a use for these, so we’re just going to chop them up and put them in whenever there is this revelation to the player.’ That’s the most direct feedback you get for the puzzles and it was kind of a late edition, [but] I think it worked incredibly well for how late we came up with it.”

According to Carlsen and Schmid, adding these tracks made a substantial difference in playtesting. Whereas previously players would interact with Cocoon and some of its more complex puzzles with uncertainty, these reaffirming melodies bolstered confidence and confirmed to players that they were on the right path. It was an addition made a mere month before Cocoon’s release, yet it seems a bit hard to imagine the final version without it.

Yet these medleys are not the only game-changing element Schmid incorporated into Cocoon. Schmid went on to explain the method he used to create a subtle-yet-powerful soundtrack that could accommodate players who might spend a bit longer in a certain area while remaining free of looping tracks.

“I’m allergic to looping music in games. It really bothers me,” Schmid said. “So I wanted to avoid that. The way I did it was something I wanted to try for a long time: writing software synthesizers that actually play as a plugin while the game is running. So they are just playing along in their own little world while you are potentially solving a puzzle [and they] might change depending on where you are or how close you are to a certain object or something like that.”

Thanks to Schmid and his team, the music in Cocoon manages to be both subtle and informative–lush, while at the same time minimalistic. It harkens back to Carlsen’s principle of balancing complexity with simplicity, and it’s an ideology that extends into the game’s art design as well.

Erwin Kho, a former freelance illustrator, joined Geometric Interactive as Cocoon’s art director and lead artist. And it becomes perfectly clear when perusing his portfolio why he was such a natural fit for the studio.

Kho described his art to me as “polygonal work inspired by ’90s computer graphics.” There’s a very clear appreciation of geometry and minimalism in his work, which he brings to life (and the third-dimension) in Cocoon. Part of the challenge of this transference, however, was reducing the sharpness and potential noise or emptiness that geometric shapes can entail.

“If you just have only all these angular shapes, it can either get really noisy really quickly or there’s something about it that feels really empty. So it was like a little bit of testing of trying to find a way to make it feel very full,” Kho said. “What we ended up doing is painting the vertices on the meshes and then we wrote our own shaders, so that we can control what those paint splotches look like. We can add different textures to them, and then you just get this particular look that is minimal, but very lush at the same time.”

Additionally, Kho was also a driving force behind the game’s narrative. The artist explained that the designs he made were largely a response to Cocoon’s gameplay, which, on its most basic level, tasks an unknown being with toting around entire worlds–similar to how an ant might carry up to 50 times its own weight. Carlsen and Schmid’s ideas inspired Kho to create an insect-like character, which then got a few other wheels turning.

“The idea of this sort of insect-inspired character, I thought that worked well,” Kho said. “Then it’s like, ‘Okay, but then why are you carrying all these orbs … why is this civilization doing this?’ So this insect being this one little drone, potentially amongst many, I felt like that also steered us in a particular direction.”

However, where this direction is exactly is a bit ambiguous–something the team says is very intentional.

Though you spend the entirety of Cocoon undertaking a metamorphosis that spans entire worlds, just why you’re going through these motions is never explained. We are never told if our protagonist’s actions are heroic, what exactly the guardians are guarding, and what freeing the moon ancestors ultimately means for the state of the universe. This is a quality Schmid said he admires in games.

“I like games where I have to think for myself to complete the story. If the story is a bit under-told, that’s my favorite because [I’m] like, ‘Oh, I’m supposed to think to complete this.’ And I hope a lot of players will have that experience as well.”

“The ending itself has a little bit of a puzzle quality to it, I think,” Carlsen added. “I think it was interesting that you can sort of apply a little bit the logic of the game and the logic of the puzzles to try and understand it in a way that, for me, makes sense at least.”

Carlsen then added that his “best case scenario” in regards to what a player would experience after playing Cocoon, would be the sensation “of being just a dot in the vastness of everything.”

“It feels very grand when you see the ending of it, but as it sort of sits with you, it also seems very small at the same time, because the universe is big. And [it] also multiple layers on a planetary level, but maybe also on a molecule level,” Carlsen said.

“It’s a fractal,” Kho added with a laugh.

“I think me and Erwin and Jakob… If you really grilled us on what this game is about, I’m not sure we’ll give the same answers,” Carlsen said. “But that is totally fine. As long as we all find it inspiring to work on and we find an experience we think will inspire others, then that is a mission accomplished.”

Cocoon was released on September 29, 2023 and is currently available on PC, Nintendo Switch, Xbox Series X|S, Xbox One, PlayStation 5, and PlayStation 4.

The products discussed here were independently chosen by our editors.

GameSpot may get a share of the revenue if you buy anything featured on our site.