Apple’s most recent financial quarter has come and gone, and the company posted (yet again) record revenues, pulling in a zillion dollars and ending its latest fiscal year with just shy of $100 billion in profit alone.

Let that sink in for a moment. $100 billion is such a large number as to be utterly incomprehensible to most of us who will never approach anywhere near even a single billion in our lifetime. It’s bigger than the gross domestic product of some countries–and not just a few of them. More than half of the countries in the world. Most of them. And again, that’s profit, not revenue, which was a soaring $316 billion, putting it in around the top 40 countries.

On the one hand, good for Apple. There was a time in living memory when the company teetered on the brink of going out of business; it’s since catapulted its way to becoming, by some estimates, the most valuable in the world. That’s a testament to the business acumen of its leaders, yes, but also to the fact that it makes great products.

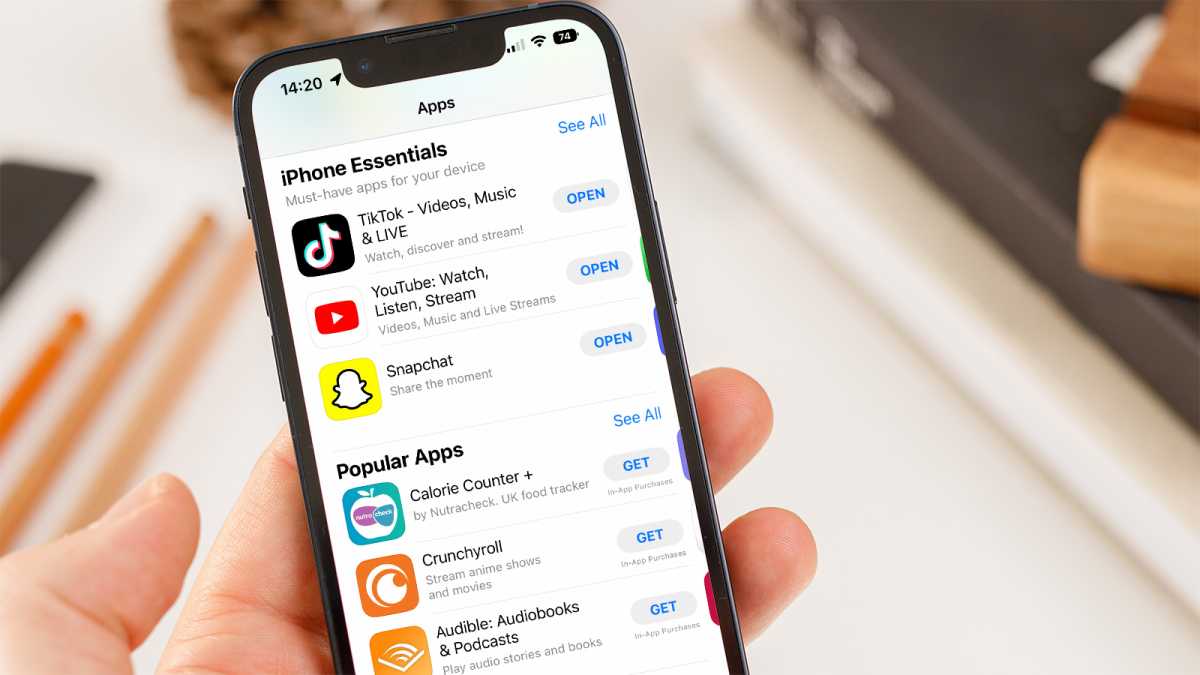

Which makes it that much more jarring to see some of the moves the company has lately made that feel, for lack of a better word, cheap: the almost pathological need to take its cut on every transaction of the App Store, the recent influx of advertising, raising prices on its services. All of these are tactics that might have benefited a hardscrabble company trying to eke out a living, but when it’s applied to one that’s making more money than most countries in the world, they come across instead as unseemly.

While there are a lot of reasons why this has been Apple’s evolutionary path, to me it boils down to three main factors.

Not dead yet

When I was a teenage Apple fan in the 1990s–yes, yes, dinosaurs still roamed the earth and I’m shaking my fist at a cloud right now to tell it to get off my lawn–Apple was on the verge of bankruptcy. The CEO’s office had a revolving door, and the company regularly pinned all its hopes on technologies that were only a little better than vaporware. This was immensely distressing to those of us who considered their products vastly superior to the masses of PC clones out there.

Spoiler: Apple, of course, didn’t go out of business. Instead, it purchased NeXT, bringing with it the return of Steve Jobs, and went on to a cavalcade of hits like the iMac, the iPod, and of course, the iPhone.

But that near-death experience left an indelible mark on the company. Like Scarlett O’Hara declaring that, with god as her witness, she’ll never go hungry again, Apple seems to labor under the paranoia that all these riches could someday suddenly vanish, leaving the company once again just steps from dissolution. The Titanic, after all, took under three hours to sink. (Not to mix my cinematic metaphors.)

The iMac was introduced and helped pull Apple out of near extinction. And sometimes the company today does what it can to make sure it never sees those days again.

Apple

That’s the main reason, I believe, that the company sat on a gigantic cash hoard for so long: it wanted a cushion to soften the blow if its business was yanked out from underneath it. It’s only relatively recently that the company’s embarked on its attempt to reach a “cash-neutral” position–something that’s proved remarkably difficult since it turns out it’s actually pretty difficult to get rid of the sheer amount of money it has.

The world goes round

When Apple averted its drop into the abyss, it was in no small part because of the return of co-founder Steve Jobs. Jobs brought with him a particular mindset, born in part from his own attitude, that served the company well in those days: Apple getting its cut. As my colleague Jason Snell recounted on the latest episode of the Upgrade podcast, Jobs seemed to hold the deep conviction that anybody making money off of Apple products–accessory makers, developers, media companies–owed the company a share of those profits.

This led to things like the Made for iPod (and later iPhone) accessory licensing programs and the iTunes Music Store’s 30-percent cut, which was later imported into the App Store.

The idea of a commission on transactions isn’t new and it’s not even that objectionable in theory: retail outlets have always had markups on the goods they sell; it’s how they pay overhead and make any profit. Agents and others regularly take a commission on their services.

Lewis Painter / Foundry

And Apple’s change in models brought benefits as well: for example, being a registered Mac developer used to cost at least $500 a year and, in some cases, much more, but the success of the iPhone app marketplace encouraged the company to drop it to a more accessible $99 per year, where it’s remained to this day. (Yes, Apple takes its percentage of an app’s proceeds to compensate, but it doesn’t change the fact that the barrier to entry is lower than it was.)

But over the years, Apple has continued to be militant about taking 30 percent of every transaction on the App Store, regardless of its involvement, and, worse, has made it less and less customer friendly to those developers wanting to take alternative routes, cracking down on any attempt to exploits loopholes. So much so that the company has found itself in the crosshairs of antitrust regulators around the world.

All of this may have served Apple well in the days when it needed to count every penny, but again, that’s far from the situation it’s in now. Instead, the aggressive tactics end up feeling uncomfortable and, at times, money-grubbing. Does the company really need to alienate its base of developers–all of whom, let’s not forget, are also its customers–in order to bolster its revenue? Where does it end?

Growth at all costs

Not all of this is directly Apple’s fault. We live, after all, in a capitalist society where maximizing shareholder profit is prized above everything else. (Though knowledgeable scholars of Adam Smith’s original treatises on the subject will point out that this mindset ignores his point that it should go hand in hand with social betterment.)

Wall Street demands growth, quarter upon quarter, year upon year–which frankly feels ridiculous when your coffers are overflowing and you literally cannot spend money fast enough. It’s akin to piling your holiday dinner table with more food than anybody could ever eat, and then demanding that next year’s spread be even more lavish. It’s a system that is, quite frankly, broken, and perhaps even a little deranged.

And it comes at a price. There’s also a flip side to the growth-at-all-costs mindset: one of those costs is customer trust. Tim Cook loves to trot out the customer satisfaction numbers for Apple’s products as though it’s the company’s north star, but that’s a trailing indicator: in many cases, you don’t know when you’ve burned through your customer trust until it’s too late. Look no further than Twitter, which is currently experiencing an erosion of user trust in real-time. Or Meta, the poster child of distrust in the tech industry, losing half of its share price. The simple fact is that no company grows forever.

The parallels are not exact, but there is a lesson to be learned here, and though changing an entire system is not a task that happens easily or quickly, who’s better positioned to make those inroads than the most valuable company in the world, with enough money to weather any resulting storm? It just needs to decide to do so.

And it’s tipped its hat in that direction. A few years back, Apple, along with 200 other large companies, puts its name on a statement that proclaimed that there’s more to business than profits, including protecting the environment, providing for employees, combatting economic inequality, and providing value to customers. While Apple has made great inroads in some of those, it’s incumbent on the most valuable company in the world to make the biggest moves. Change, as they say, begins at home, and Cupertino should take a close look at what it’s sacrificing for the sake of a few dollars more.