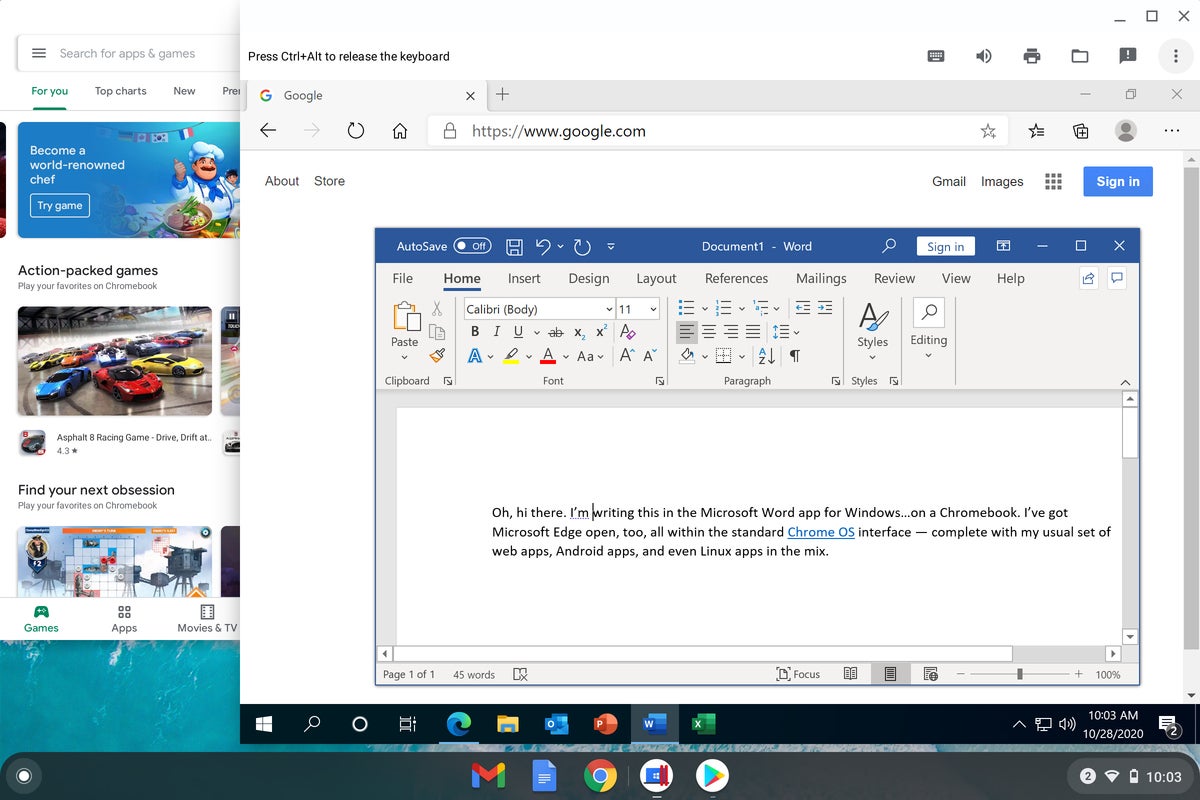

Hi. I’m writing this in the Microsoft Word app for Windows…on a Chromebook. I’ve got Microsoft Edge open, too, all within the standard Chrome OS interface — complete with my usual set of web apps, Android apps, and even Linux apps in the mix.

Worlds are colliding, in other words. And if my first official taste of this wild new reality tells me anything, it’s that the traditional boundaries we tend to think about with platforms and operating systems no longer apply. At least, not when you’re using a Chromebook.

Let me back up a sec and set the stage for my surreal little experiment here: Back in June, Google announced it was working with a company called Parallels to bring Windows app support into the Chrome OS environment. The magic works via a virtual machine that’s installed on the Chromebook and then made to run locally on the device, which means you can use virtually any Windows program as if it were a local app — whether you’re online with an active internet connection or not.

For the moment, at least, this whole thing is designed exclusively with the enterprise in mind: The Parallels Windows-on-Chrome-OS setup is available only on specific, approved hardware — high-end systems, basically, with an Intel Core i5 or i7 processor, at least 16GB of RAM, and 128GB of storage recommended — and only in company-wide configurations. It comes at a cost, too: a cool 70 bucks per user per year.

And lemme tell ya: Having had the chance to use it extensively this week, I think this is gonna be a pretty intriguing option and one that has the potential to exponentially expand Chrome OS’s appeal.

Welcome to the world of Windows…on Chrome OS

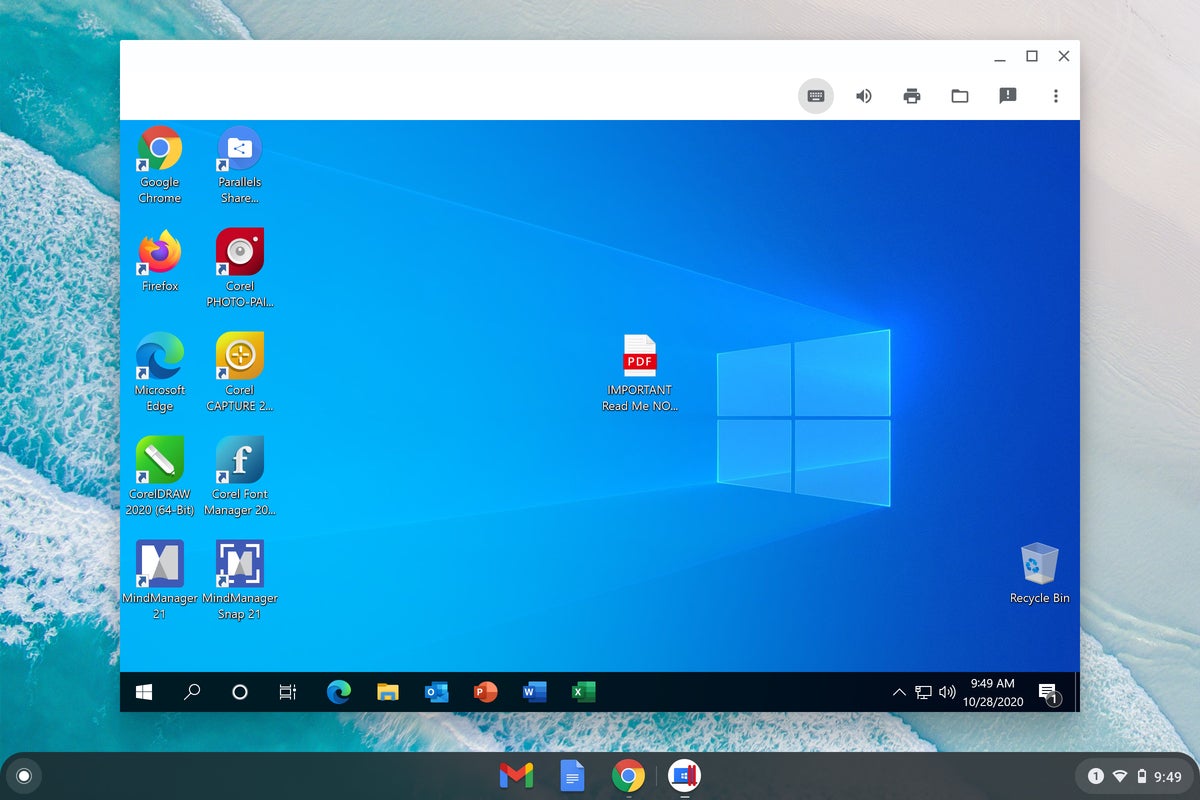

First things first, let’s get one thing out of the way: Running Windows apps on a Chromebook in this new Parallels-provided setup isn’t exactly like running a regular, native program on your device. The nature of the whole “virtual machine” thing means you end up running Windows itself within an app-like window. And it’s within that window that you then find, open, and use the traditional Windows software.

Whew. Got all that?!

JR

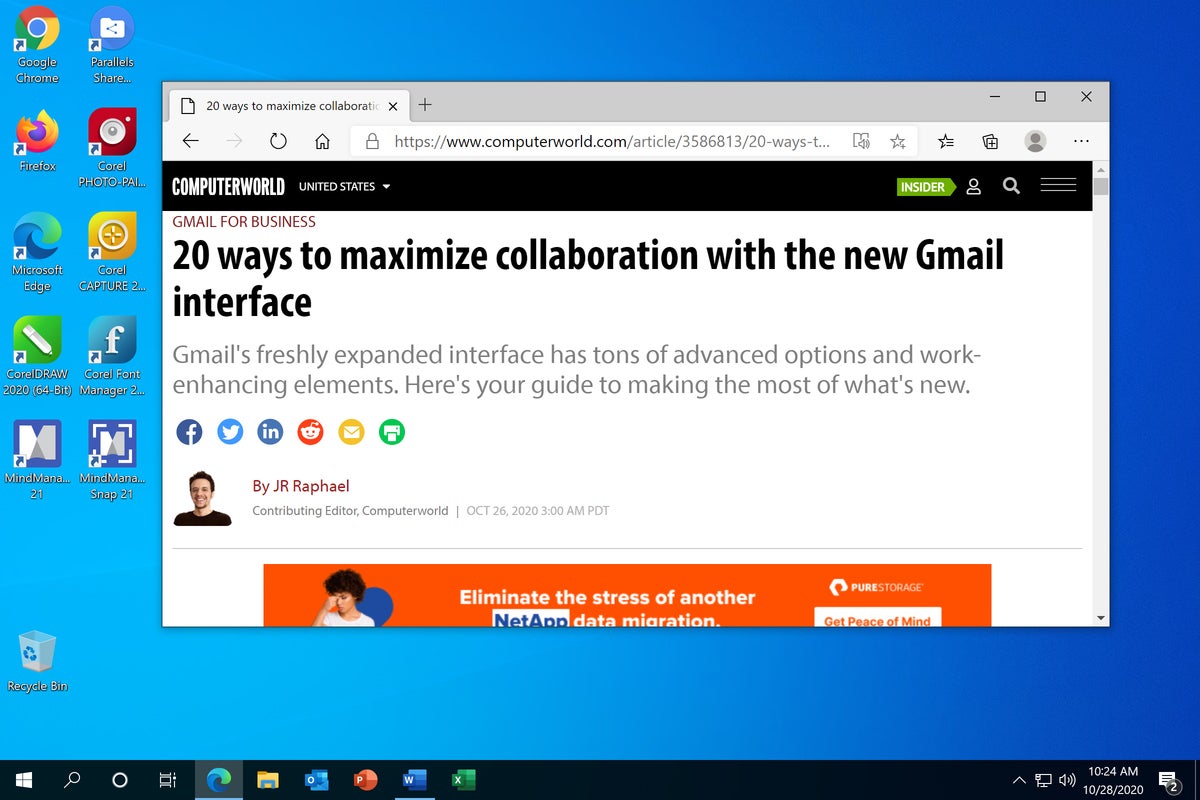

JR The Windows desktop, within Chrome OS (whoaaaa…).

Suffice it to say, that makes things inherently a little…awkward. It’s easy to see why: You ultimately have a second desktop within your regular Chrome OS desktop. It feels like you’re using Chrome Remote Desktop or another similar sort of remote-access tool, but while the experience itself is somewhat similar to that on the surface, this Windows installation is actually on the Chromebook itself and not just streaming to you via a standalone Windows computer.

Even so, it’s kind of odd — because it is a second desktop and effectively a separate operating system running inside your primary operating system. (Paging M.C. Escher…) That means you end up seeing Windows boot up whenever you first open the system:

JR

JR Welcome to the matrix: Windows booting up locally, in its own window, on a Chromebook.

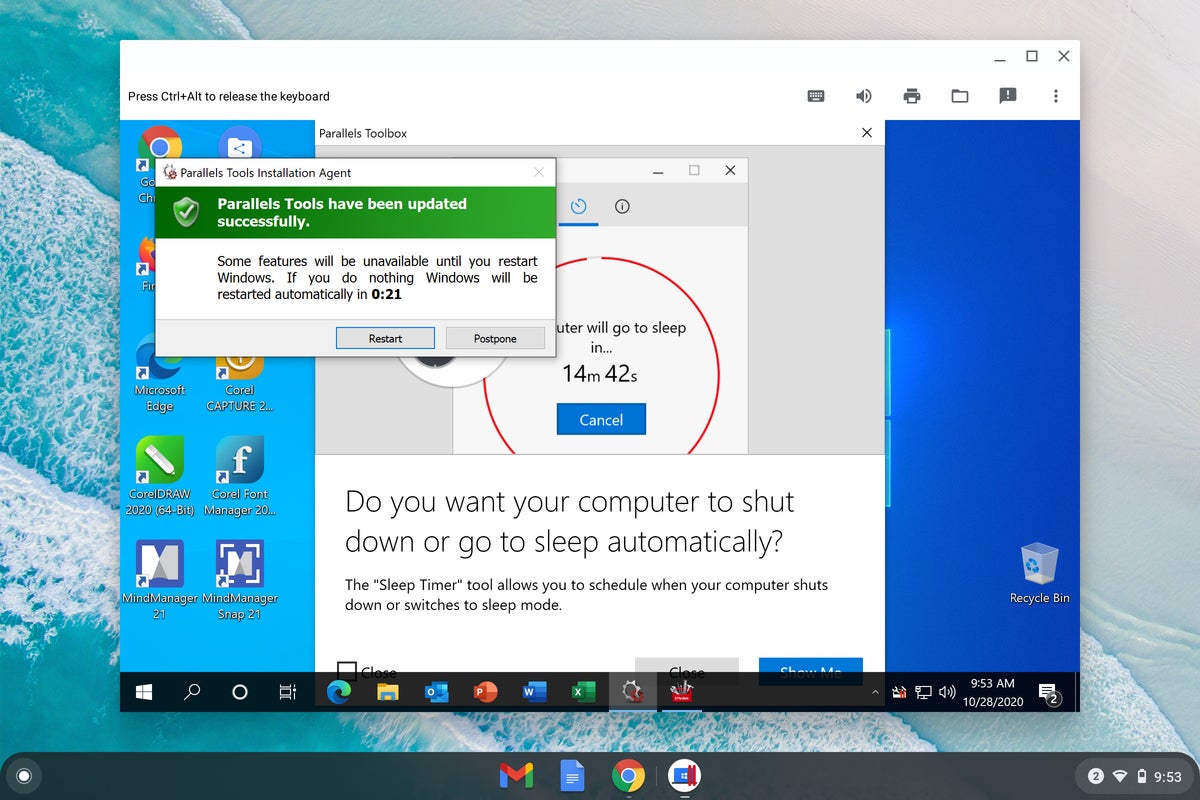

And you occasionally get Windows-specific notifications within that inner Windows desktop, including prompts to restart the Windows system (an action that has no effect on the greater Chrome OS system) in order to apply software updates.

JR

JR Well, this is awkward: One operating system preparing to restart within another.

Once you get past the weirdness of it all, though, y’know what? It mostly just works and does what it’s meant to do — and does it rather well. You simply open up any program you want within the Windows environment, just like you would on a regular Windows computer, and then use it right then and there. You can open up multiple programs and manage ’em with the standard Windows multitasking methods. All your Windows stuff just always exists within that inner Windows, erm, window.

JR

JR Windows windows within the Windows window.

By and large, in my experience — testing this on my own personal Pixelbook, which has a Core i5 processor and 8GB of RAM (notably less than the recommended 16GB level) — things have run smoothly and without any of the annoying lag you often experience when using a more typical remote virtualization solution. I’ve run into a couple of instances where the Windows environment has started acting slightly weird for a handful of seconds, but that’s really been more the exception than the rule.

There are, however, some quirks. By default, for instance, pressing Alt-Tab takes you to the Chrome OS app switcher. And some of the time, pressing Tab by itself opens up a Windows-specific app switcher when you’re focused on the Windows desktop. It doesn’t always do that, though — it frequently just acts as a regular Tab key and does what the Tab key would normally do, even when you’re using the Windows system — and I’ve yet to figure out any rhyme, reason, or consistency with how and why its function changes.

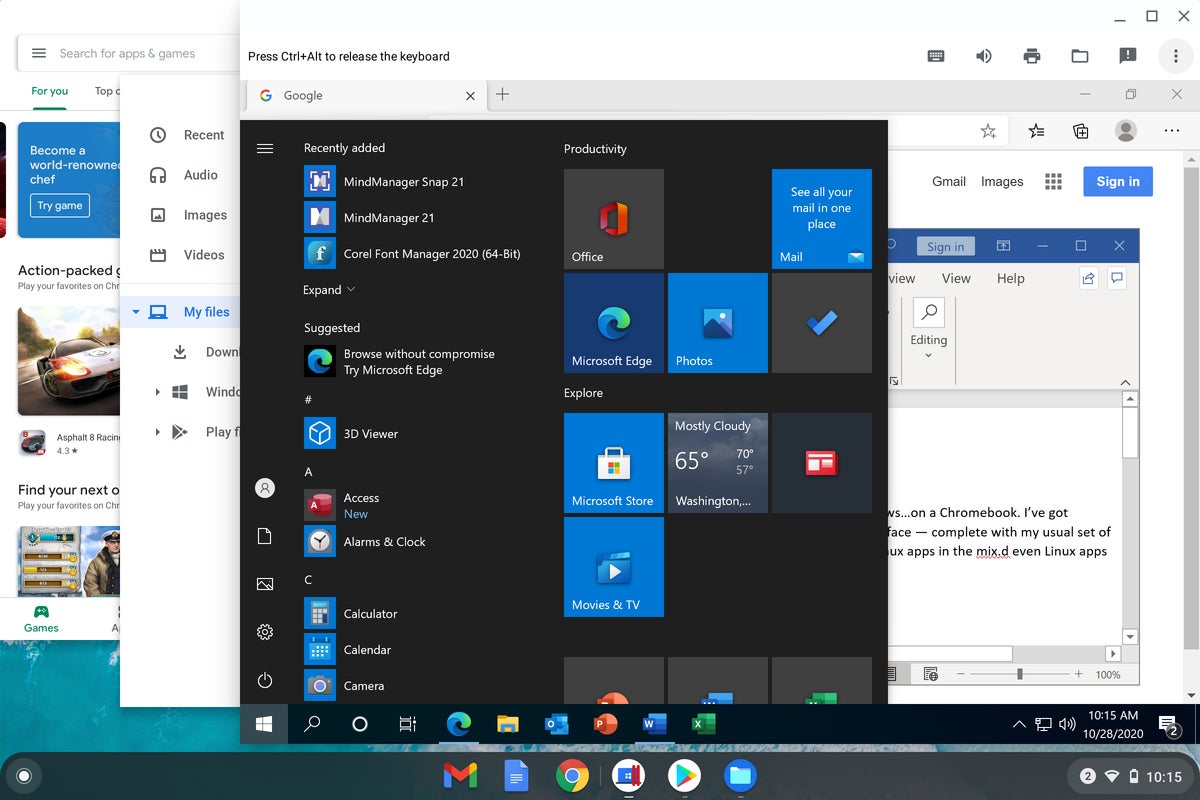

The Chrome OS Search/Launcher key, meanwhile, automatically detects the current context and works appropriately — which means if you press it while you’re using anything in Windows, it opens up the Windows Start menu instead of pulling up the standard Chrome OS launcher.

JR

JR So many launchers, such little time.

That’s a little confusing, but I’m not sure there’d be any better way to handle it, given this arrangement.

Those minor oddities aside, Parallels and Google have clearly worked closely together to make the Windows and Chrome OS experiences feel as complementary and connected as possible. The system clipboards, for instance, work seamlessly across both environments — meaning you can copy something from anywhere within Chrome OS and then paste it anywhere in Windows (or vice-versa). You can set web links within Windows to open in any Windows-based browser or in a standard Chrome OS browser window, depending on your preference.

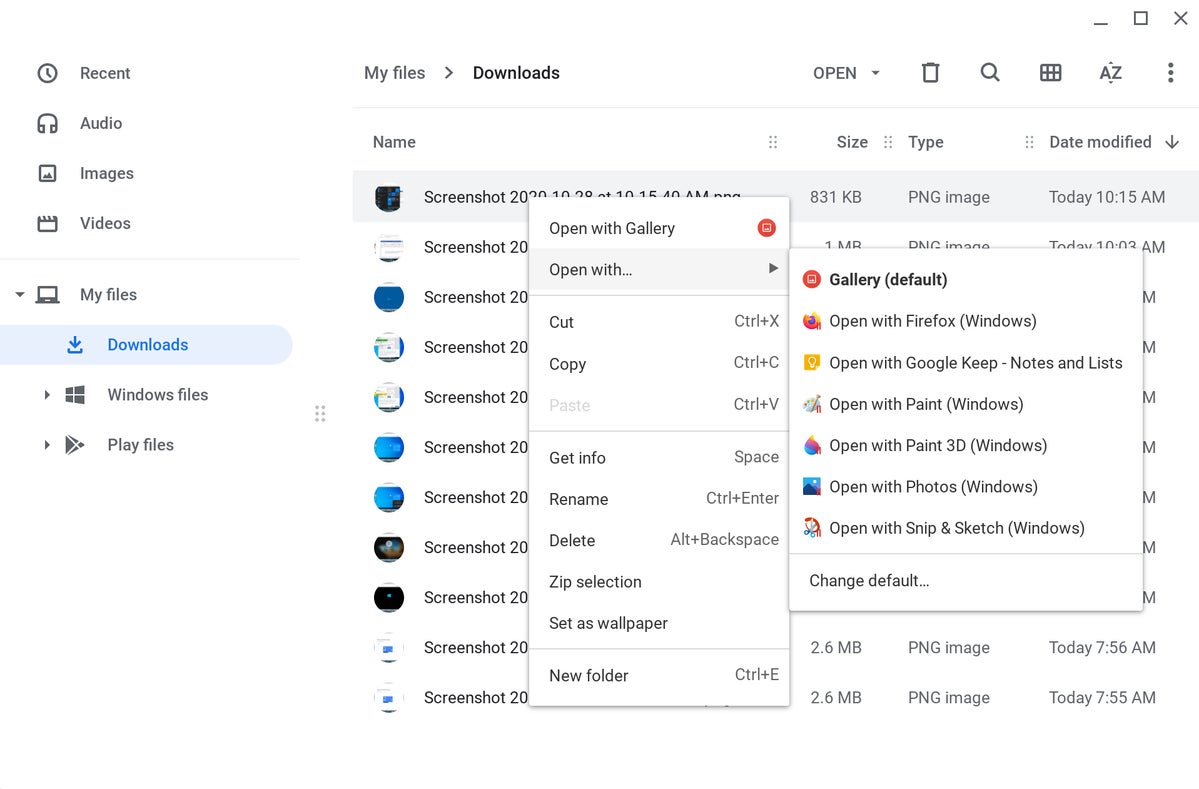

And when it comes to files, you can actually set any file type to open within a Windows app by default system-wide, if you’re so inclined — so that, for instance, spreadsheets would automatically open in the Windows Excel app or images would open in a Windows-based editing tool whenever you click on ’em from anywhere on the computer.

JR

JR Separate yet connected: the Chrome OS-Windows story.

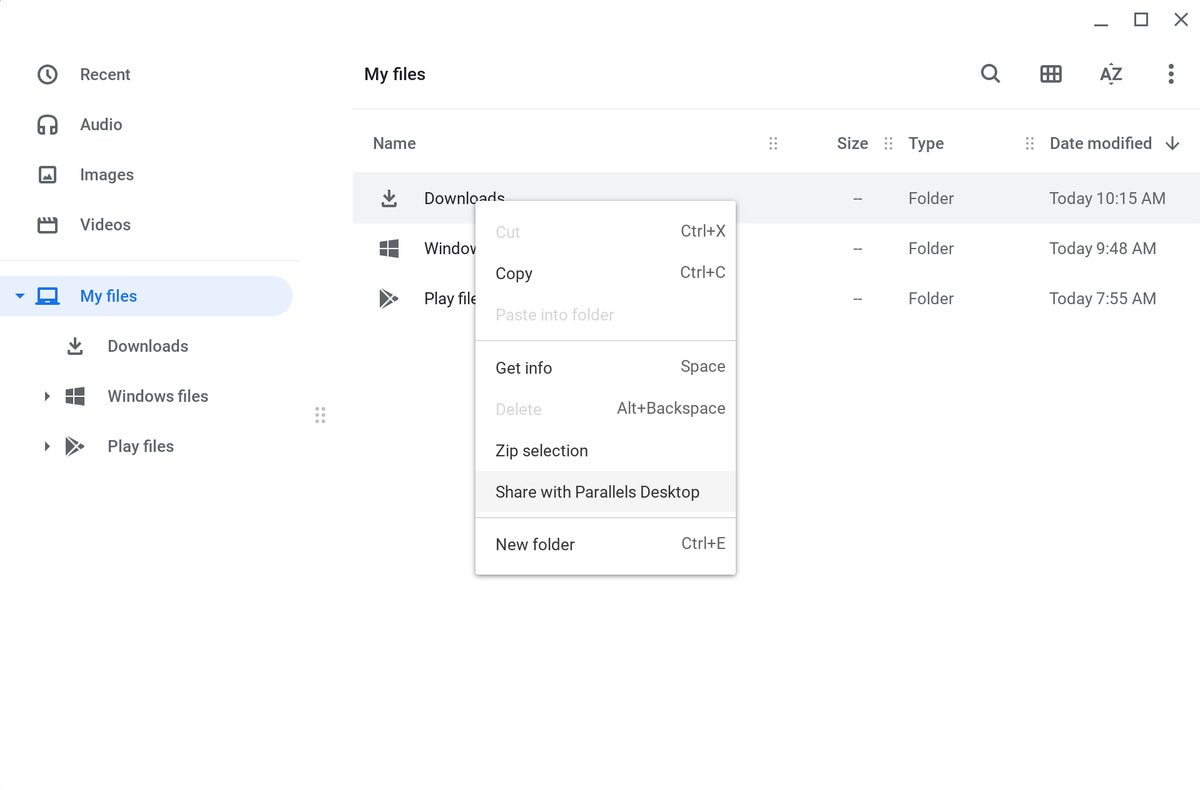

Files from the Windows side of things are integrated into the standard Chrome OS Files app, too, which means they’re always available to you from anywhere on the Chromebook — regardless of whether Windows is running or not.

JR

JR The shared Windows-Chrome OS file system, as seen from the Chrome side.

And in a twist that’ll feel familiar to anyone who’s used Linux apps on Chrome OS, you can share any folder on the Chromebook with the Windows system and then have its contents be available anywhere within Windows.

JR

JR Chrome OS folders only become accessible to Windows programs if you deliberately set them to be that way.

In terms of visuals, the Windows desktop window automatically adjusts its resolution as you size it (by clicking and dragging on any of its edges, just like any other window). And if you want to focus on the Windows side of things exclusively, without having that desktop look like a mere window within another desktop, you can hit the maximize key in the Chromebook keyboard’s function row to make it take up your entire display and have it be as if you were just using a Windows computer.

JR

JR Wait — what kind of computer is this, again?

What else? Any printers available within Chrome OS are automatically available within Windows apps without any extra effort required. About the only thing that doesn’t “just work” right now, in fact, is audio: While you can play audio from a Windows app without issue, recording isn’t yet supported within the Windows side of things (though Parallels tells me that’s in the works and will be corrected in a future update).

Finally, as for the apps themselves, pretty much anything that can run in Windows can work in this environment — including custom business applications along with standard office apps, photo and video editing utilities, and so on. It’s up to each individual company to configure the Windows environment and determine what’s available within it (and to implement any necessary licenses, of course).

That makes it hard to see how this same setup could easily apply to individual, consumer Chromebook users — but hey, you never know how things might evolve over time.

Windows apps on Chrome OS and the bigger Chromebook picture

Google, for its part, is framing this new setup explicitly as a method for providing “legacy application support” — a deliberate-seeming way of emphasizing that this is meant to be viewed as a bridge to the past for companies that still require some traditional, local software in addition to the increasingly common web-based alternatives.

Whether it’s a bridge to the past or an acknowledgement of the present, though, the presence of this Windows workaround accomplishes one very specific and extremely consequential result: It solidifies Chrome OS’s position as the “everything” operating system — a platform-defying universe where you can run web apps, Android apps, and Linux apps side by side, as if they were one and the same, and now where you can add Windows software into that same mix as well.

The Windows apps aren’t quite as native-feeling as their web, Android, and Linux cousins, given the necessity for them to run in that virtual machine environment, but practically speaking, they offer the same exact benefit. And once you get accustomed to the way they operate and figure out what you actually need, they’re really pretty natural to bring into your workflow.

If you know you’re gonna be using Excel, for instance, you can open it up and then maximize it within the Windows desktop and set the Windows taskbar to autohide itself. And at that point, it’s not much different from having any standard Chrome OS app open and available on your Chromebook.

JR

JR Just another app there on the right — one that you almost wouldn’t even realize is running within a Windows virtual machine.

Sure, it’d be nice if you could pin specific Windows programs to the Chrome OS shelf (a.k.a. the taskbar) and access ’em without having to go through the whole Windows desktop interface — but this setup seems less about trying to make Windows apps a native part of the Chrome OS environment and more about providing a way to fill in the gaps. And, more specifically, it’s aimed at companies that have been close to being able to go the Chromebook route but have had a few lingering roadblocks remaining.

For any such organizations, as I’ve put it previously, the presence of this new Parallels option means the low-cost, low-maintenance, and low-security-risk computing setup they’d perhaps previously considered but couldn’t quite justify is suddenly now viable. For Google, that means the lucrative business market it’s been trying to break into with Chrome OS is suddenly now attainable. And for regular ol’ individual users of Chromebooks, it means the platform could suddenly start seeing a new injection of large-scale interest — which has the potential to trickle down and lead to even more hardware diversity and software development across the entire ecosystem.

When you look back to the dead-simple, no-frills framework Chrome OS launched with 11 years ago, it’s crazy to think how far things have come — and how dramatically the once-humble Chromebook has evolved from that original “browser in a box“-like vision to the all-in-one, “everything” system it is today.

Sign up for my weekly newsletter to get more practical tips, personal recommendations, and plain-English perspective on the news that matters.

Copyright © 2020 IDG Communications, Inc.