One boring day during the pandemic, security researcher Craig Hays decided to do an experiment. He wanted to leak an SSH username and password into a GitHub repository and see if any attacker might find it. Hays thought he’d have to wait a few days, maybe a week, before anyone noticed it. Reality proved more brutal. The first unauthorized login happened within 34 minutes. “The biggest eye-opener for me was how quickly it was exploited,” he tells CSO.

Over the first 24 hours, six different IP addresses connected to his honeypot a total of nine times. One attacker tried to install a botnet client, while another one attempted to use the server to launch a denial-of-service attack. Hays also saw someone who wanted to steal sensitive information from the server and someone else who was just looking around.

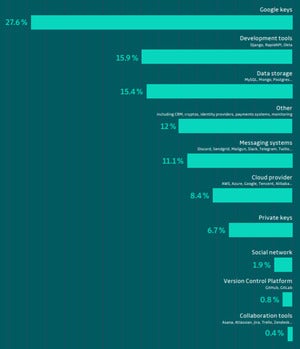

The experiment showed him that threat actors are constantly scanning GitHub and other public code repositories looking for sensitive data developers leave behind. The volume of secrets, including usernames, passwords, Google keys, development tools, or private keys, keeps rising as companies transition from on-premises software to the cloud and more developers work from home. This year alone, there will be at least a 20% increase in exposed secrets compared to the year before, says Eric Fourrier, co-founder of France-based security startup GitGuardian, which scans public repositories to identify data attackers might take advantage of.

How hackers find GitHub secrets

Hackers know GitHub is a great place to find sensitive information, and organizations such as the United Nations, Equifax, Codecov, Starbucks, and Uber have paid the price of negligence. Some companies might argue that they are not at risk because they don’t work with open-source code, but the truth is more nuanced; developers often use their personal repository for work projects. According to the State of Secrets Sprawl on GitHub report, 85% of the leaks occur on developers’ personal repositories and only the remaining 15% within repositories owned by organizations.

Devs leave shell commands history, environment files, and copyrighted content. Sometimes they make mistakes because they try to streamline their processes. For instance, they might include their credentials when they write the code because it’s easier to debug. Then, they might forget to remove it and commit. Even if they do a deletion commit later or a push force to erase the secrets, that private information can often still be accessed in the Git history.

GitGuardian

GitGuardianMost common types of secrets exposed on GitHub

“I find a lot of passwords in old versions of files that have been replaced with newer and cleaner versions without the passwords in,” Hays says. “The Git commit history remembers everything, unless you deliberately and explicitly delete it.”

Both junior and senior developers can make mistakes. “Even if you’re a great developer and you’re educated on the issue, at some point, while coding late at night, you can make a mistake, and stuff happens,” Fourrier said. “Leaking secrets is a human mistake.”

GitGuardian

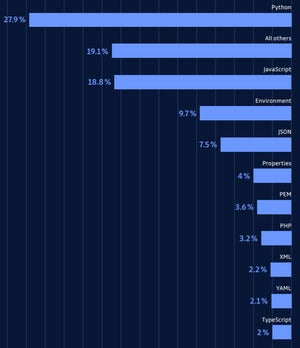

GitGuardianMost common types of files found exposed on GitHub

While any developer is prone to errors, those just entering the job market usually leak the most secrets. Many years ago, when she was a software engineering student, Crina Catalina Bucur set up an AWS account for development purposes and received a $2,000 bill out of which only $0.01 was rightfully hers to pay.

“My project was an aggregated file management platform for around ten cloud storage services, including Amazon’s S3,” she said. “This was before GitHub offered free private repositories, so my AWS access key and the corresponding secret key got published along with the code to my public repository. I didn’t stop to think about it, but even if I had, I don’t think I’d have given too much consideration.”

A few days later, she started receiving emails from AWS warning her that her account was compromised, but she didn’t read them carefully—until she received the bill. Luckily for her, AWS support waived the extra charges. Bucur made several mistakes that were exploited by hackers, including hardcoding the keys for convenience and publishing them to a public code repository.

Today, hackers who want to find errors like these need few resources, says Hays. He is a bug bounty hunter in his free time and often relies on open-source intelligence (OSINT)—information that anyone can find on the web if they know where to look for it. “My method of choice is to manually search using the standard Github.com interface,” he said. “I use search operators to restrict to particular file types, keywords, users, and organizations, depending on which companies I’m targeting.”

Some tools can make the process quicker and more efficient. “Attackers run automated bots that scrape GitHub content and extract sensitive information,” security researcher Gabriel Cirlig at HUMAN says. These bots can be left running all the time, which means that hackers can detect mistakes in a matter of seconds or minutes.

Once a secret is found, attackers can easily exploit it. “For instance, if you find an AWS key, you have access to all the cloud infrastructure of the company,” Fourrier says. “It’s super simple to target developers working for a specific company and try to look at some of the assets of the company.” Depending on the nature of the secrets, hackers can do many things, including launch supply chain attacks and compromise the safety of a company’s clients.

How companies can protect secrets from GitHub leaks

As the volume of secrets increases, companies need to become better at detecting them before it’s too late. GitHub has its own “secret scanning partner program,” which finds strings of text that look like passwords, SSH keys, or API tokens. GitHub has partnered with over 40 cloud service providers to remediate API keys exposed in public repositories automatically.

“We’re continually looking to expand these partnerships to better protect the ecosystem,” a GitHub spokesperson tells CSO. “We currently revoke over 100 exposed GitHub API keys every day, often safely introducing new developers to the importance of credential security as we do so.”

Hays said that the “Secret scanning partner program” is a step in the right direction, as it makes it harder for attackers to find valid credentials. He says, though, that the initiative is not perfect. “It still leaves a gap for when people accidentally check in their own SSH keys, passwords, tokens, or anything else that is sensitive,” he says. “This is a lot harder to detect and manage as there are no partnered credential providers to ask questions like ‘Is this real? Do you want to revoke it? Should one of us tell the owner about it?'”

Meanwhile, he advises developers to be conscious of how they’re writing and deploying their code. “One of the first things to get right is adding the correct settings to a .gitignore file,” he said. “This file tells Git and therefore GitHub.com which files shouldn’t be tracked and uploaded to the internet.”

Some security startups are also trying to fill the gap. GittyLeaks, SecretOps, gitLeaks, and GitGuardian aim to offer a few more layers of protection to both business users and independent professionals. Some detect leaked secrets within seconds, allowing developers and companies to take immediate action. “We scan all your code on your software through the entire development lifecycle, the Docker container, different types of data,” Fourrier says. “We find the secrets and try to revoke them.”

Ideally, though, the best strategy is to not leak secrets at all or leak as few as possible and raising awareness on this matter can help with that. “Educating developers for writing secure code and proactively stopping bots is always better than playing whack-a-mole with leaked secrets,” Cirlig says.

Copyright © 2021 IDG Communications, Inc.