Many of us have become used to building our own PCs, inserting graphics cards and SSDs into a motherboard. Intel chief executive Pat Gelsinger sees a sea change coming to the chip industry where the chips inside your PC are “assembled” in very much the same way.

This matters. For years, a PC’s processor has been a relatively simple affair, made by a single company on a single process technology. But something happened in March of this year that will allow Intel and other companies to mix and match specific pieces of logic inside of a single chip, in almost the exact way PC makers build PCs.

[ Further reading: The best CPUs for gaming ]

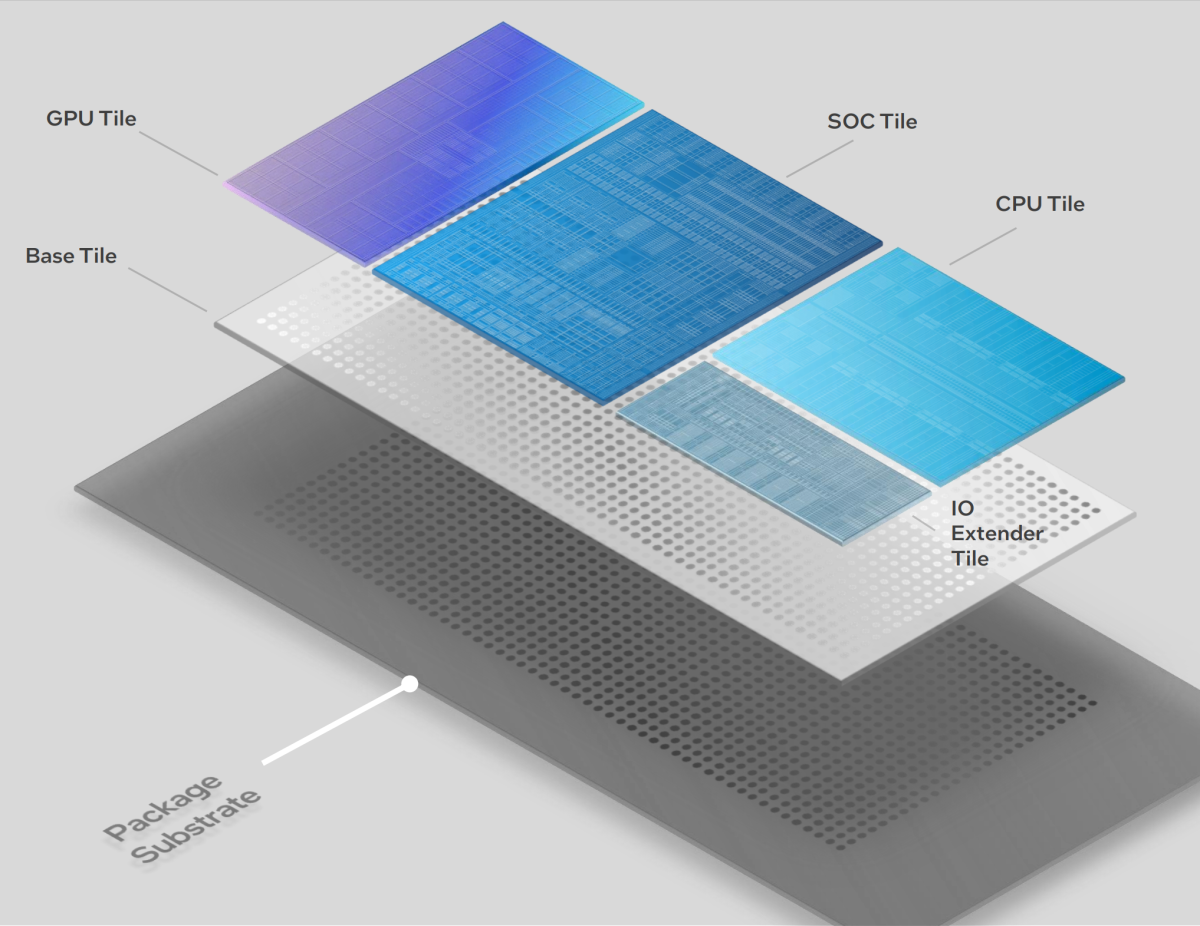

That was the introduction of the Universal Chiplet Interconnect Express (UCIe), and the concept is simple enough. Use different “tiles,” or chiplets, plug them into a base tile, and connect all of them via the UCIe standardized interface to build the chip of the future. It’s pretty easy to see this “base tile” as a motherboard of sorts, with various components attached to it: graphics, I/O, and so on.

What UCIe does is present a truly standardized, open interface to allow this to happen. If you’ve followed the chip industry closely, you may know that “standards” don’t always apply to everyone; that’s why Intel Core-based notebooks have Thunderbolt ports, while those powered by AMD’s Ryzen chips include USB 4 ports — they’re functionally equivalent, yet different. But UCIe is supported by almost all of the key players: AMD, Intel, Microsoft, Qualcomm, Arm, Samsung, and TSMC, among others. The only exception, for now, is Nvidia.

Intel has been iterating on chip and chiplet design for decades.

Mark Hachman / IDG

Gelsinger has lobbied hard for the Chips for America Act, which was signed into law earlier this month, providing $52 billion for the American chip industry. Last year, Gelsinger pledged a return to greatness by investing in new fabs and launching Intel’s first foundry business. But Gelsinger said at the Hot Chips academic conference this week that he doesn’t want to just build fabs for Intel. He wants to build “systems foundries” for multiple customers, all based on UCIe.

Gelsinger was asked whether Intel’s system foundry, and UCIe, would enable a mix-and-match approach, where customers can buy chiplets from different vendors and assemble them together. He agreed.

“Yeah, that’s it,” Gelsinger replied. “That’s my expectation, that UCIe becomes like PCIe [PCI Express].”

“We expect UCIe to be the equivalent of that,” Gelsinger added. “You may say, hey, I’m getting two of the chiplets from Intel. I’m getting one of the chiplets coming from a TSMC factory, maybe the power-supply components coming from TI. Maybe there’s an I/O component coming from GlobalFoundries and, of course, Intel has the best 3D packaging technology so they’re going to be the on assembling all those chipset chiplets into the marketplace, but maybe it’s another OSAT [Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test] provider as well.”

Meteor Lake: the next step

We’ve been building to this point for some time, though the important work has been done in the last five years. The most high-profile integration of chiplets from multiple sources was Kaby Lake-G, the 2017 combination of an Intel Core CPU and AMD’s Radeon GPU.

Two other technologies have been critical to Intel’s development: what it calls EMIB, which extends chiplets along a 2D plane, and Foveros, which allows chip dies to be vertically stacked, in 3D. In 2019, Intel combined the two into what it calls co-EMIB. There are a number of terms that get bandied about: disaggregation, tiles, and chiplets. They all mean pretty much the same thing: LEGO, but with semiconductors.

We’re going to start to see more of this concept come to fruition next year with Intel’s “Meteor Lake” chip, which Intel detailed at Hot Chips. At the bottom is the package substrate. Above, there’s the “base tile.” And above those are the various tiles, specifically the GPU tile, the CPU tile, the SOC tile (media, imaging, and display, essentially), and the I/O extender tile (the chipset). Intel CPUs have traditionally contained two dies within a single package; now, there are essentially four.

Mark Hachman / IDG

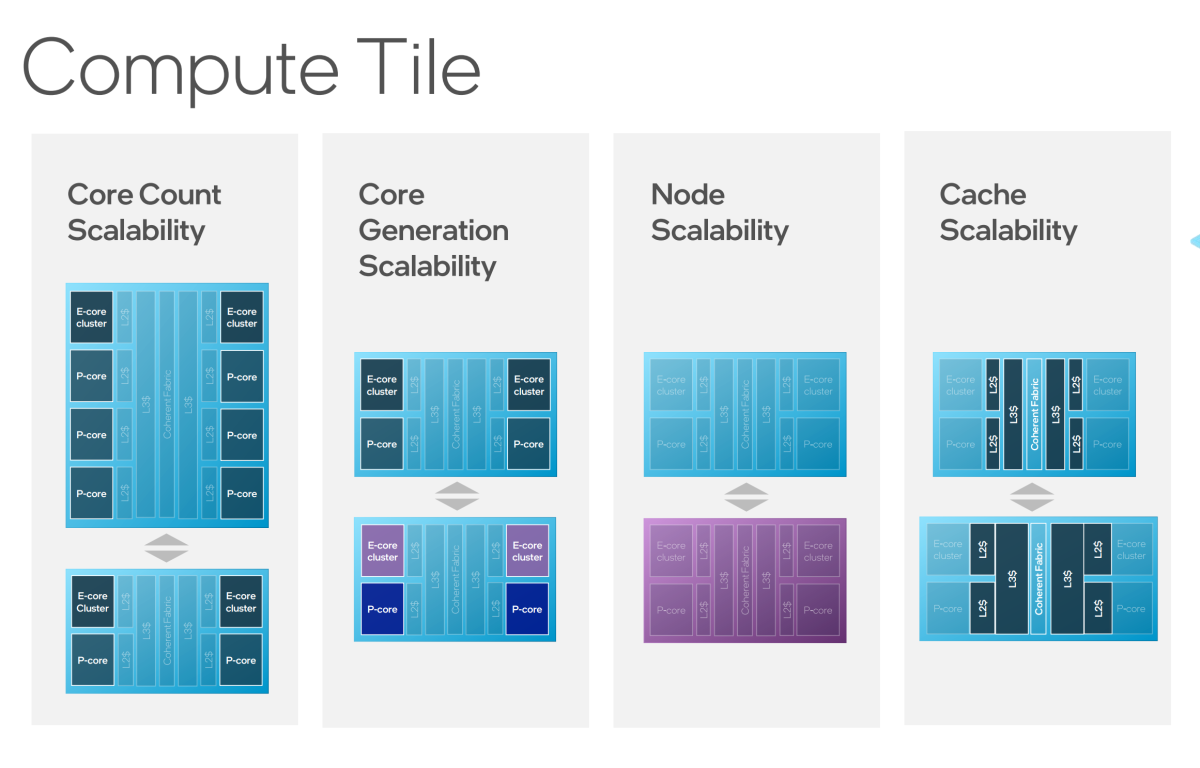

What Intel let slip earlier in the week is that we’re already seeing Gelsinger’s disaggregation vision come to fruition, as most of Meteor Lake’s components are made by TSMC, not Intel, but will be assembled into the Meteor Lake chip. At Hot Chips, Intel executives showed how each tile could be manufactured with variations, such as multiple arrangements of power and efficiency cores, GPUs with more processing units, and so on. It also doesn’t matter if some tiles are made on an Intel 4 process, or a TSMC fab line, or whatever, as they can be dropped in and reused in future processor generations. (Meteor Lake does not use UCIe, however, as the specification was finalized just a few months ago.)

We do know that it works, though. Intel has functioning samples of Meteor Lake, which it has successfully booted inside of a PC, executives said.

Will performance suffer? Will it be more expensive?

That’s a sea change from Intel’s historical stance: build a single, powerful “monolithic” chip and stick it in a PC, a server, and (hopefully) a notebook, too. What was very interesting is that Intel’s Hot Chips presentation for Meteor Lake (and its successor, Arrow Lake) addressed the question directly. Can Intel get monolithic performance with disaggregated architecture benefits?

The answer? Intel believes it can get close. There will always be a performance and power penalty moving data from tile to tile, Wilfred Gomes, an Intel fellow in microprocessor design, said at Hot Chips. But that “disaggregation tax,” in Intel’s view, will only be about 2 to 3 percent and outweighed by the flexibility disaggregation provides. (Intel didn’t clarify whether it was talking about performance, or power, and what it is comparing those numbers to.)

Mark Hachman / IDG

Flexibility affects your wallet, too. Intel’s goal is to achieve chips with a trillion transistors in them by the end of the decade. But not every chip can be manufactured without errors. A lithography error, or just some stray radiation, can essentially kill off the entire chip. (Or part of it — it’s why Intel’s F-series chips lack a functional GPU.) It’s much cheaper to toss a hundred-million transistor tile in the trash than a far more expensive trillion-transistor monster.

It’s important to note that while AMD’s Ryzen is moving ahead on chiplets, too (and offers performance that competes with and even has outshined Intel’s own), Intel is taking the lead in terms of talking openly about mixing and matching chiplets and tiles. AMD, by contrast, is taking more of a monolithic approach, despite Ryzen using multiple chiplets.

The bottom line

So what does all of this mean for you? Two things, basically. For one, the increasing complexity and flexibility that Intel’s disaggregation strategy enables in chips like Meteor Lake means that they’ll be increasingly hard to describe; we already have a mix of performance and efficiency cores, base and turbo clock speeds, integrated graphics cores, and more in 12th-gen CPUs. Soon, spec sheets could be even more dizzying.

The second, though, is more interesting, even if it still feels something in the realm of sci-fi, for now. A world in which someone (a company? you?) will be able to order up a chip in much the same way you order a sandwich or a car, made to order, is a powerful vision. Chip nerds realize that programmable logic or even ASICs have offered similar capabilities for decades. But for the mainstream enthusiast, this semi-custom future enabled by UCIe may mean a dramatic rethinking of how your PC’s processor is made.