An uninterruptible power supply (UPS) offers a simple solution: it’s a battery in a box with enough capacity to run devices plugged in via its AC outlets for minutes to hours, depending on your needs and the mix of hardware. This might let you keep internet service active during an extended power outage, give you the five minutes necessary for your desktop computer with a hard drive to perform an automatic shutdown and avoid lost work (or in a worst case scenario, running disk repair software).

In terms of entertainment, it could give you enough time to save your game after a blackout or—perhaps more importantly—give notice to others in a team-based multiplayer game that you need to exit, so you’re not assessed an early-quit penalty.

This article was updated July, 2022 to add a link to our IOGear GBB1000N UPS review.

A UPS also doubles as a surge protector and aids your equipment and uptime by buoying temporary sags in voltage and other vagaries of electrical power networks, some of which have the potential to damage computer power supplies. For from about $80 to $200 for most systems, a UPS can provide a remarkable amount of peace of mind coupled with additional uptime and less loss.

UPSes aren’t new. They date back decades. But the cost has never been lower and the profusion of options never larger. In this introduction, I help you understand what a UPS can offer, sort out your needs, and make preliminary recommendations for purchase. Later this year, TechHive will offer reviews of UPS models appropriate for home and small offices from which you can make informed choices.

Uninterruptible is the key word

The UPS emerged in an era when electronics were fragile and drives were easily thrown off kilter. They were designed to provide continuous—or “uninterruptible”—power to prevent a host of a problems. They were first found in server racks and used with network equipment until the price and format dropped to make them usable with home and small-office equipment.

This inexpensive AmazonBasics Standby UPS ($80) features 12 surge-protected outlets, but only six of them are also connected to its internal battery for standby power.

Any device you owned that suddenly lost power and had a hard disk inside it might wind up with a corrupted directory or even physical damage from a drive head smashing into another part of the mechanism. Other equipment that loaded its firmware off chips and ran using volatile storage could also wind up losing valuable caches of information and require some time to re-assemble it.

Hard drives evolved to better manage power failures (and acceleration in laptops), and all portable devices and most new computers moved to movement-free solid state drives (SSDs) that don’t have internal spindles and read/write heads. Embedded devices—from modems and routers to smart devices and DVRs—became more resilient and faster at booting. Most devices sold today have an SSD or flash memory or cards.

It’s still possible if your battery-free desktop computer suddenly loses power that it may be left in a state that leaves a document corrupted, loses a spreadsheet’s latest state, or happens at such an inopportune moment you must recover your drive or reinstall the operating system. Avoiding those possibilities, especially if you regularly encounter minor power issues at home, can save you at least the time of re-creating lost work and potentially the cost of drive-rebuilding software, even if your hardware remains intact.

A more common problem can arise from networking equipment that has modest power requirements. Losing power means losing access to the internet, even when your cable, DSL, or fiber line remains powered or active from the ISP’s physical plant or a neighborhood interconnection point, rather than a transformer on your building or block. A UPS can keep your network up and running while the power company restores the juice, even if that takes hours.

When power cuts out, the UPS’s battery kicks in. It delivers expected amounts over all connected devices until the battery’s power is exhausted. A modern UPS can also signal to a computer a number of factors, including remaining time or trigger a shutdown through built-in software (as with Energy Saver in macOS) or installed software.

In the event of a blackout, CyberPower’s software will gracefully shut down a computer while it operates on battery power from its CP800AVR UPS.

One of the key differentiators among UPSes intended for homes and individual devices in an office is battery capacity. You can buy units across a huge range of battery sizes, and the higher-capacity the battery, the longer runtime you will get or more equipment you can support with a single UPS. In some cases, it may make sense to purchase two or more UPSes to cover all the necessary equipment you have, each matched to the right capacity.

Batteries do need to be replaced, although it can be after a very long period. A UPS typically has a light or will use a sound to indicate a battery that needs to be replaced, and it might indicate this via software running on the computer to which it’s connected.

With great power, comes great power conversion

UPSes for consumer and small-business purposes come in standby and line interactive versions. Standby units keep their battery ready for on-demand, automatic use, but it’s otherwise on standby, as its name indicates. A line interactive version feeds power through an inverter from the wall to connected devices while also charging the battery. It can condition power, smoothing out highs and lows, and switch over to the battery within a few milliseconds. (Other flavors are much more expensive or intended for critical systems and higher power consumption.)

A few years ago, the price differential was high enough that you had to really balance the need for particular features against cost. Now, you may want to opt for a line interaction UPS because of its advantages, which include less wear and tear of the battery, extending its lifetime. Batteries are relatively expensive to replace, at a good fraction of the original item’s purchase price, so keeping them in fit condition longer reduces your overall cost of ownership.

A UPS isn’t just about providing power when it’s interrupted, though, and that’s another place that a standby and line interactive approach vary.

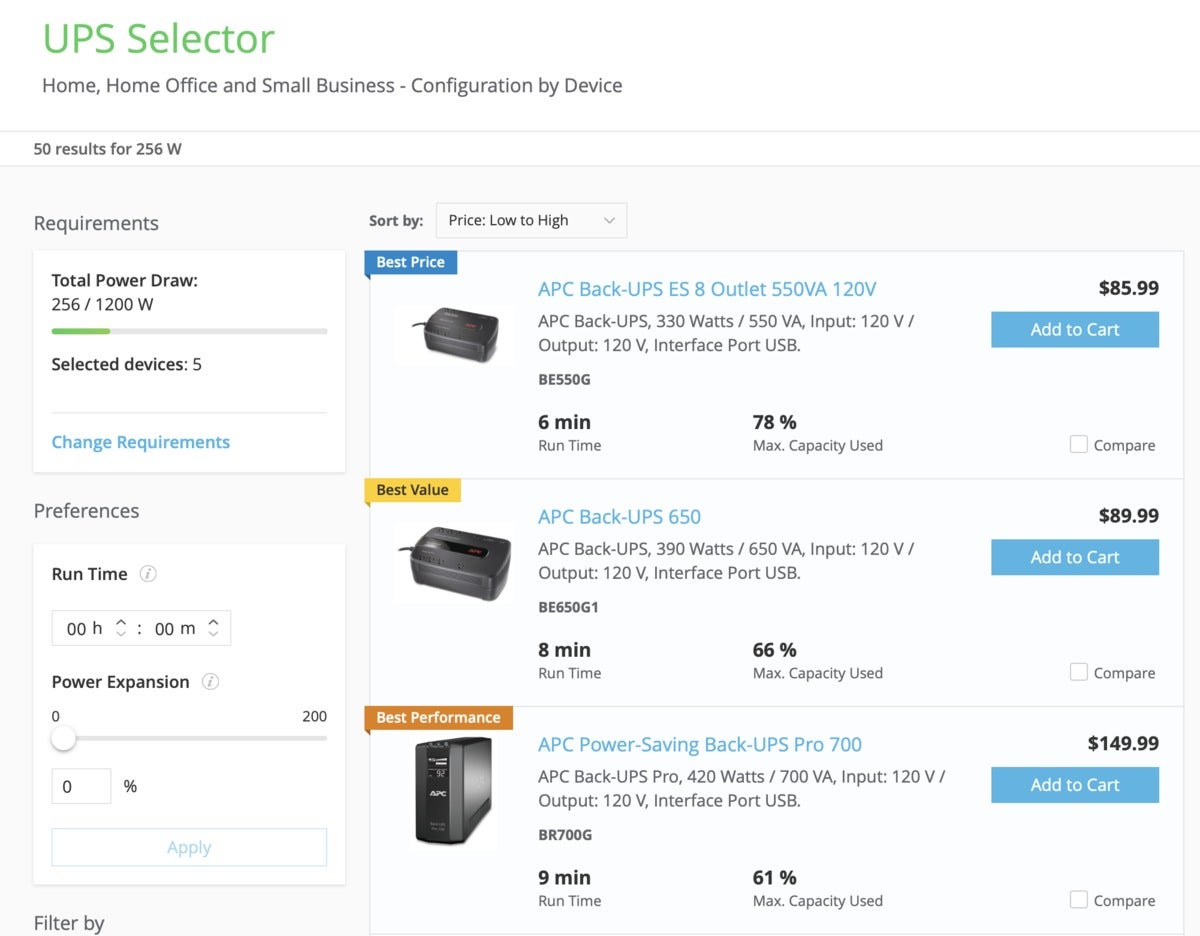

APC’s website offers a handy tool that will help you decide which of its UPSes fit your requirements, based on total power draw and how long you’ll need battery power for your components.

These three voltage fluctuations can happen regularly or infrequently on power supplied by your utility:

- Surges: Utilities sometimes have brief jumps in electrical power, which can affect electronics, sometimes burning out a power supply or frying the entire device. Surge protection effectively shaves off voltage above a certain safe range.

- Sags: Your home or office can have a momentary voltage sag when something with a big motor kicks on, like a clothes dryer or a heat pump—sometimes even in an adjacent apartment, house, or building.

- Undervoltage (“brownouts”): In some cases with high electrical usage across an area, a utility might reduce voltage for an extended period to avoid a total blackout. This can mess with motor-driven industrial and home equipment—many appliances have motors, often driving a compressor, as in a refrigerator or freezer. With electronics, extended undervoltage has the potential damage some power supplies.

A standby model typically relies on dealing with excess voltage by having inline metal-oxide varistors (MOVs), just as in standalone surge protectors. These MOVs shift power to ground, but eventually burn out after extensive use. At that point, all the UPS models I checked stop passing power through. (That’s as opposed to most surge protectors, which extinguish a “protected” LED on their front, but continue to pass power.)

For power sags and undervoltage, a standby model will tap the battery. If it happens frequently or in quick succession, your UPS might not be up to the task and provide enough delay that a desktop system or hard drive loses power long enough to halt its operating system or crash.

A line interactive UPS continuously feeds power through a conditioner that charges the battery and regulates power. This automatic voltage regulation, known as AVR, can convert voltage as needed to provide clean power to attached outlets without relying on the battery. With a line interactive model, the battery is used only as a last resort.

There’s one final power characteristic of a UPS that can be found in both standby and line interactive models: the smoothness of the alternating current generation produced by the model from the direct current output by its battery. Alternating current reverses its power flow smoothly 60 times each second, and a UPS must simulate that flow, which can be represented as an undulating sine wave.

The Tripp Lite Smart1500LCDT is a line-interactive UPS, meaning it feeds connected devices conditioned power while it charges its battery at the same time. In the event of a blackout, it will switch to battery power within a few milliseconds.

A UPS might produce a pure sine wave, which adds to cost, or a stairstepped one, in which power shifts more abruptly up and down as it alternates. A rough simulated sine wave can be a showstopper for certain kinds of computer power supplies, which have components that interact poorly with the voltage changes. It could cause premature wear on components or cause them to outright shut down or cause additional damage.

If your device has active power factor correction (PFC) or incorporates fragile or sensitive electronics, especially for audio recording, you likely need a pure sine wave. It’s not always easy to figure out if your device has active PFC; when in doubt, opt for a pure sine wave—the additional cost has come way down.

Even for equipment that isn’t susceptible to power-supply problems, a stepped sine wave can cause a power supply to emit a high-pitched whine when it’s on battery power.

One final UPS feature that may also be helpful: less-expensive models have one or more LEDs to indicate certain status elements, like working from backup power or the internal battery needing to be replaced. Others have an LCD screen (sometimes backlit) that provides a variety of information, sometimes an excessive amount, which may be viewable through software installed on a connected computer.

All UPSes have built-in audible alarms for outages, and some are quite loud.

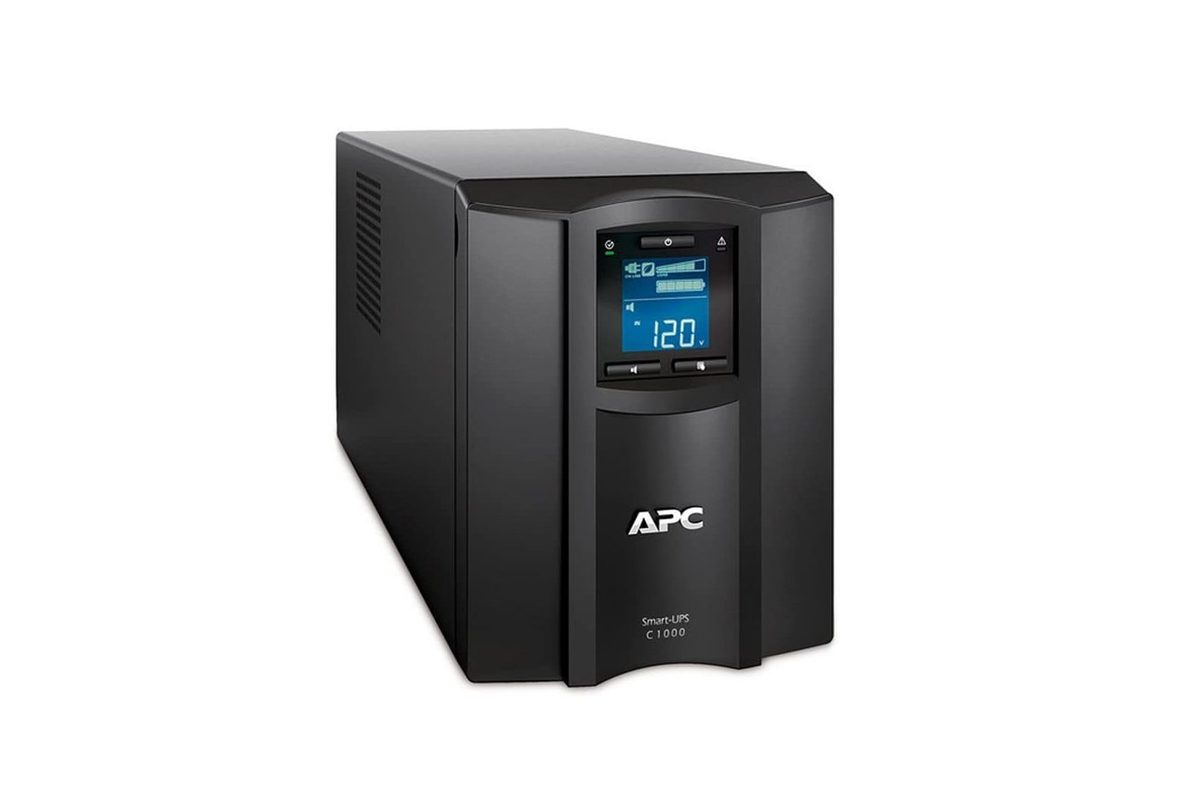

A UPS that puts out a pure sine wave, such as this APC SMC1000, is your best choice if you’re operating sensitive equipment, such as audio-recording gear. An LCD display is also useful for monitoring the UPS’s status.

Determining your UPS needs

Most of us have two main scenarios to plan for: keep the network up, and prevent our AC-powered computers from abruptly shutting down. These involve very different choices in hardware and configuration.

One common element between both, however: having enough outlets spaced correctly to plug all your items directly in. Most UPSes feature both battery-backed outlets and surge-protected outlets that aren’t wired into the battery. You need to study quantity and position, as it is strongly recommended you don’t plug a power strip or other extensions into either kind of UPS outlet, as it increases the risk of electrical fire.

That can be particularly tricky if you have large “wall wart” style AC adapters or wider-than-average AC plugs.

Scenario 1: Keep the network up

Examine all the devices that make up your network. That may include a broadband modem, a VoIP adapter for phone calls, one or more Wi-Fi routers, one or more ethernet switches, and/or a smart home hub. Because you may have these spread out across your home or office, you might wind up requiring two or more UPSes to keep the network going.

If you have a modem, router, and switch (plus a VoIP adapter if you need it) all in close proximity, you might be able to live without other parts of your networking operating during an outage. It’s also probable that you already have this hardware plugged into a surge protector. (These devices tend to not benefit from a UPS’s sag/undervoltage assistance, as their DC adapters tend to provide power in a larger range of circumstances.)

You might already have a simple battery backup built into or included with one or more pieces of equipment. Many smart home hubs have built-in battery backups. And since government regulators typically require a multi-hour battery backup for VoIP service, your broadband modem or VoIP adapter might include an internal battery for that reason.

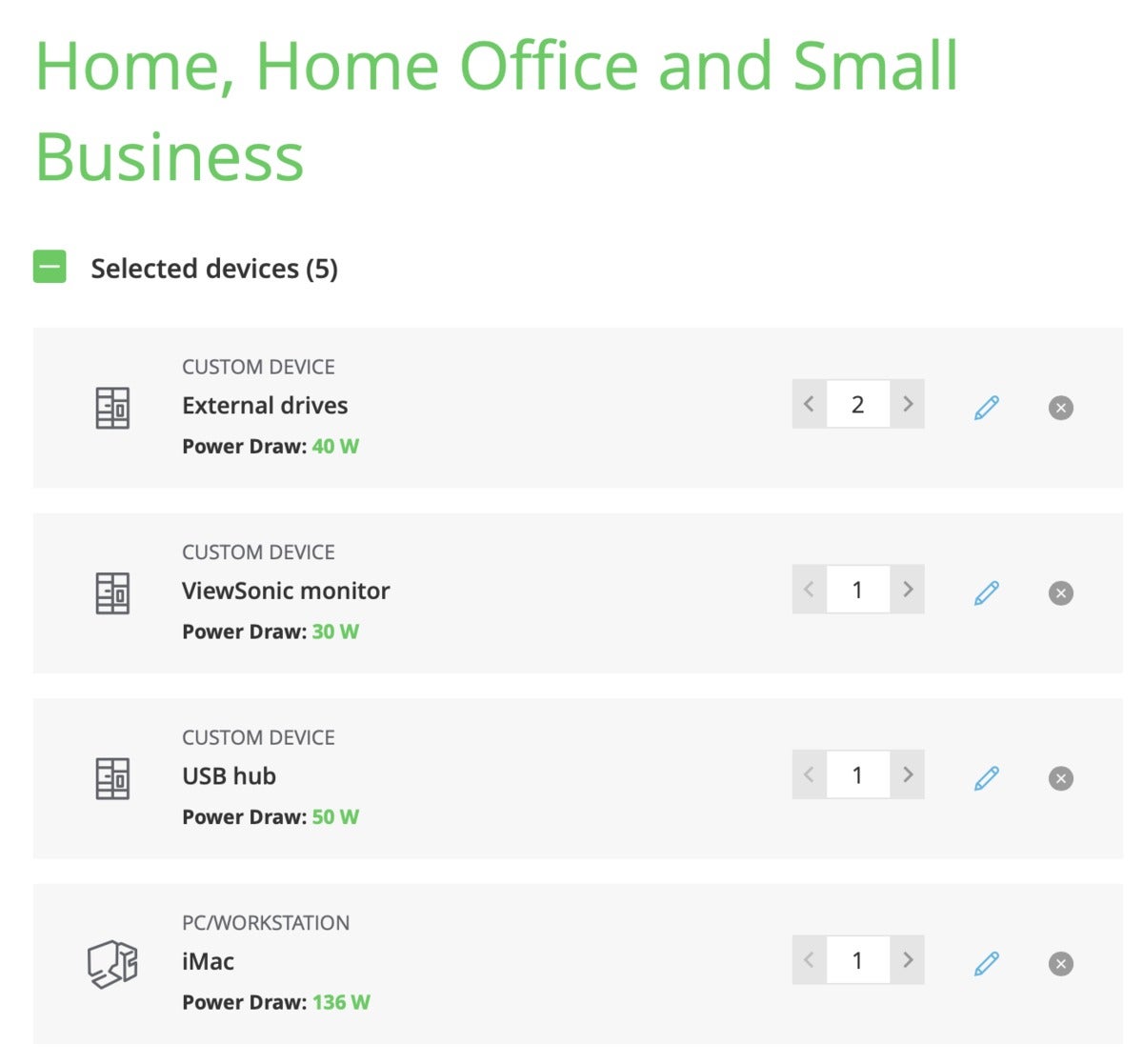

To find out the size of UPS you need, check the specs on all your equipment. This is usually molded in plastic in black-on-black 4-point type on the underside of the gear or on a DC converter that you plug directly into a power outlet or that comes in two parts with a block between the adapter to your device and a standard AC outlet cord. The numbers you are looking for are either DC voltage and amperage, like 12 volts and 1.5 amps, or total wattage, like 18 watts.

Add up these quantities, and that can let you use planning tools to find the right unit. For instance, APC offers an extended runtime chart that lists wattage and runtime for each of its units. You can also use a calculator on the site in which you add devices or watts and it provides a guide to which units to purchase and how much time each could operate at that load.

For most combinations of gear and affordable units, you should be able to keep network equipment running for at least an hour entirely on battery power. Spend more or purchase multiple units, and you could boost that to two to eight hours.

To determine the size of UPS you’ll need, add up the the number of watts that each device will draw. You can find this information on each one’s power supply or AC adapter.

Scenario 2: Bridge power blips and shut down a computer

Your goal here is to make sure all your devices that need to continue running have enough power to do so across a short outage and to shut down—preferably automatically—during any outage that lasts more than a few minutes.

There are two separate power issues to consider: the electrical load that devices connected to the UPS’s battery-backed outlets add up to, and the capacity of the internal battery on the UPS, which determines how long power can flow at a given attached load. (The outlets only protected against power surges have a far higher power load limit that computer equipment won’t exceed.)

Start by calculating the total wattage for all the equipment you’re going to connect, just like with network gear. Most hardware will show a single number for watts or a maximum watts consumed; if it only shows amperes (or amps), multiple 120 (for volts) times the amps listed to get watts. In my office, I have an iMac, an external display, a USB hub, and two external hard drives. That adds up to about 250W.

With that number, you can examine the maximum load on a UPS, which is often perplexingly listed using either volt-amperes (VA) and watts or both. Although volts times amps and watts should be equal, UPS manufacturers use a different formula, which is probably a bad idea. Watts on a UPS is volts times amps times power factor, or the efficiency with which a power supply on a computer or other device provides power from its AC input to its components.

A UPS uses a USB cable to communicate with a connected computer, triggering software on the machine to gracefully short down while operating on battery power.

In practice, you can still add up all your devices in watts, and use that as a gauge to find a UPS that exceeds that amount by some margin: you can’t exceed the UPS load factor with your equipment, or it won’t function. (If a UPS is rated only in VA, multiply that number by a power factor of 0.6 or 60% to get the bottom level in watts.)

With that number in hand, you can then look over the runtime available on models that can support your total load, consulting the figures, charts, or calculators noted above that manufacturers provide to estimate how many minutes you get on battery-only power.

With my iMac set up above of 250W, I have several options in the $100 to $150 range that have a power load maximum far above that number and which can provide five or more minutes of runtime.

It’s also critical to pick a UPS model that includes a USB connection to your desktop computer, along with compatible software for your operating system. While macOS and Windows have built in power-management options that can automatically recognize compatible UPS hardware, you might want additional software to tweak UPS settings (like alarm sounds) or to provide detailed reports and charts on power quality and incidents.

The OS power-management tools and software from UPS makers give you options to create safe, automatic shutdown conditions. You can define a scenario like, “If the outage lasts more than three minutes or if the battery’s power is less than 50 percent, begin an immediate safe shutdown.”

It’s also important to be sure that all your running apps can exit without losing data and not halt the shutdown. For instance, an unsaved Word file might prevent Windows from completing a shutdown. In macOS, the Terminal app refuses to quit by default if there’s an active remote session, but it can be configured to ignore that.

Picking the right UPS

With all that in mind, here’s a checklist to go through in evaluating a UPS:

- What kind of time with power during an outage do you require? Long for networked equipment; short for a computer shutdown.

- How many watts do your equipment consume? Calculate your connected devices’ total power requirements.

- Do you have frequent or long power sags? Pick line interactive instead of standby.

- With a computer, does it rely on active PFC? If so, pick a model with a pure sine wave output.

- How many outlets do you need for power backup? Will all your current plugs fit in the available layout?

- Do you need to consult the UPS status frequently enough or in detail that an LCD screen or connected software is required?

We’re in the process of reviewing several uninterruptible power supplies and will update this stories with links to those reviews as we finish them. Stay tuned.