In the opening of You Will Die Here Tonight (YWDHT), my Resident Evil-inspired super-cop solved a confusing book-based puzzle and ventured into a secret underground lab, where she was then met with a monologue from her ally-turned-enemy. To my surprise, this Albert Wesker-like big bad then shot my character dead–all in the first 15 minutes. It was like starting a Resident Evil game in the final scene and then getting a dark ending where the villains prevail. With a touch of meta commentary on the genre, this unconventional introduction was an intriguing start, but also the last part of the game I truly enjoyed, as the game thereafter ran through too-common horror tropes without cleverly subverting or enhancing them ever again.

In the aptly titled You Will Die Here Tonight, Resident Evil is the blueprint for a two- to four-hour-long isometric, survival-horror game with a touch of roguelite progression. That fun intro I detailed would’ve been a neat story track to stay on, as the big bad who seems to prevail quickly discovers there’s another unseen hand, more powerful than her own, that is pulling the strings. But the game oddly drops this pretense in favor of a roguelite system whereby, when a character dies, you assume the role of another member of A.R.I.E.S. (the legally distinct and totally-not-S.T.A.R.S. division of police officers) keeping all story items with the opportunity to recover other scraps if you can find the body of your predecessor.

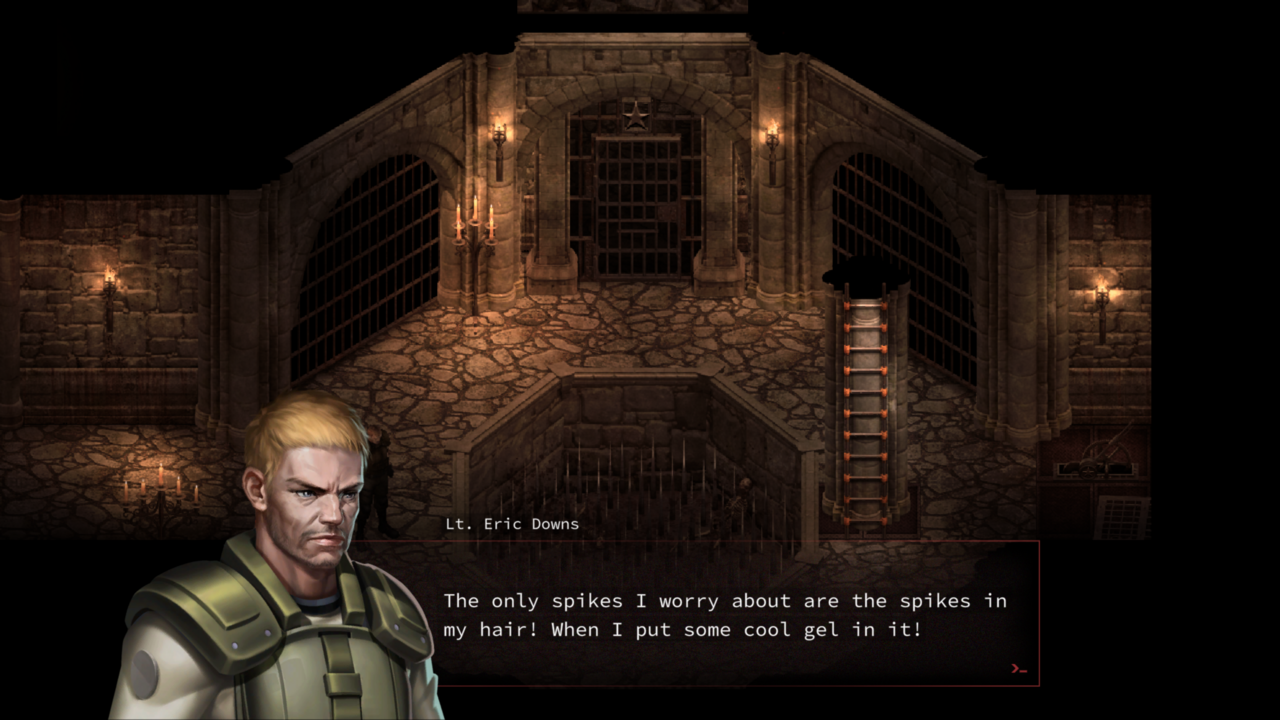

The dissonance between that story-heavy opening scene and what follows winds up feeling like two different games that somehow both made it into the final version. Each character plays the same but offers different text lines, with a few seeming quite serious and others offering bothersome jokes that wouldn’t land at some middle school lunch tables. The mansion-like setting with secret labs, a torture dungeon, and some high-end offices and libraries is very much akin to a setting from Capcom’s seminal series, and the roundabout way you navigate this space–solving convoluted puzzles and gathering various items to open doors and collect new weapons–is all meant to take you back to the late ’90s, when games like this were most prevalent.

The problem, however, is the genre has improved for the better since then, and YWDHT feels like a reversion to something worse. Some of the puzzles and encounters feel downright unfair, like the game’s name is a promise more than a threat. Once, I had to escape a charging boulder, but the character’s sprinting speed and the nearest corner to duck into seemed to mean I was meant to die unavoidably, and I did, which allowed my next character to move past where the mass of rock originally sat. Other times, the puzzles could find the right balance between obtuse and satisfying, but never often enough.

Though the game uses an isometric angle most of the time, it switches into first-person for combat, which is a neat idea but winds up being quite boring in execution. Surrounded by multiple plain-looking zombies, headshots were always very easy to land. Conserving ammo and switching to my knife was a wise choice when facing few enemies, but the visuals made it hard to measure the distance between a zombie and me, leading to me frequently slashing at the air over and over until a zombie shambled into the pointy end.

The only time it was a major issue was when the game threw so many zombies at me at once, so quickly, that I again took it as a promise that the game wanted me to go through the story having lost at least a few characters. But to that end, I always felt indifferent from a narrative standpoint. The story doesn’t characterize anyone much past that cool intro or the aforementioned corny jokes, so when I’d lose a character, its only practical effect was to make me worry about what happened when I lost them all.

Eventually, I purposely got them all killed to see what would happen, only to be met with an arcade-style “continue” screen, which picked up right where I left off and fully refreshed my roster of playable characters. This became an even more perplexing design conundrum for me to ponder. Why threaten the loss of characters, and furthermore, why seemingly script some deaths into the game if nothing happens once they’re all gone? Again, this made YWDHT feel like a collection of disparate horror game ideas, some of which may have worked better in isolation, somewhat tweaked, or with other conflicting ideas excluded. But in totality as they are here, they just don’t mesh.

While the puzzles sometimes clicked and the story had at least that one early bright spot, the audiovisual aspects of the game are only straining. The game strives for a retro aesthetic, but does this faithfully only in that it’s grainy and drab. There’s no strong use of shadows–just lit and unlit areas, the latter of which you can’t enter anyway. Many locales within the vast castle-like setting are an eyesore. It’s hard to imagine a game chasing the nostalgia of late-’90s horror games without including a memorable soundtrack, but such is the case here. Music is almost uninvolved, surprisingly, and things like monster growls and ambient audio don’t do much at all to fill in a scene.

The game is brief and polished, so I think it’s possible someone who loves the games You Will Die Here Tonight is affectionately cribbing could manage to enjoy this too, but probably only if they’re really itching for something else to play. There’s no shortage of games resurrecting this style, and many of them have been memorable. Others have been worse, but at least some have been interesting in their shortcomings. The overarching issue with You Will Die Here Tonight is that the death alluded to in its title can be attributed to boredom.