In some ways, the Zoom videoconferencing app seemed to come from nowhere this year — even though it’s been around since 2013 and has long been highly regarded for its ease of use.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic erupted, first in China, then around the world. On Feb. 26, Zoom announced it had already added more new users in the first two months of 2020 than it had in all of 2019. Within a month, as the pandemic spread, office workers suddenly found themselves jumping on daily Zoom calls from the comfort of home in a desperate attempt to keep in touch with colleagues.

Fast forward another few months, and many of those same workers are officially suffering from Zoom fatigue.

Few companies have seen the kind of growth — and boosted name recognition — as quickly as the San Jose, Calif.-based videoconferencing platform. That growth also led to growing pains. In April — after a slew of security and privacy issues arose — Zoom CEO Eric Yuan announced that the company would stop developing new features for 90 days to address the problems. (This is when “Zoom-bombing” became a common phrase.)

Despite the furore, the company that same month announced it had 300 million daily meeting participants.

With most countries still in at least a partial lockdown and coronavirus spikes continuing, videoconferencing is here to stay. (Zoom is apparently so sure that’s the case that in July it launched Zoom for Home, an ill-conceived piece of hardware that assumed everyone participating on a video call wants as much of their home in view as possible.)

Zoom for Home

Zoom for Home Zoom for Home marked a sharp pivot by the company into hardware.

Despite some missteps, the company appears poised to continue to grow and evolve, making it an important tool for companies looking to ride out the pandemic with workers distributed far and wide.

Here’s a look at what Zoom is, does and how it works.

What is Zoom? The basics

Founded by former Webex executive Eric Yuan in 2011 and officially launched in 2013, Zoom’s aim is to make videoconferencing easy and accessible. The platform provides video services for enterprise, consumer and educational customers, and its relatively simple setup (compared to competitors) took it to Unicorn status in 2017 and an IPO in 2019.

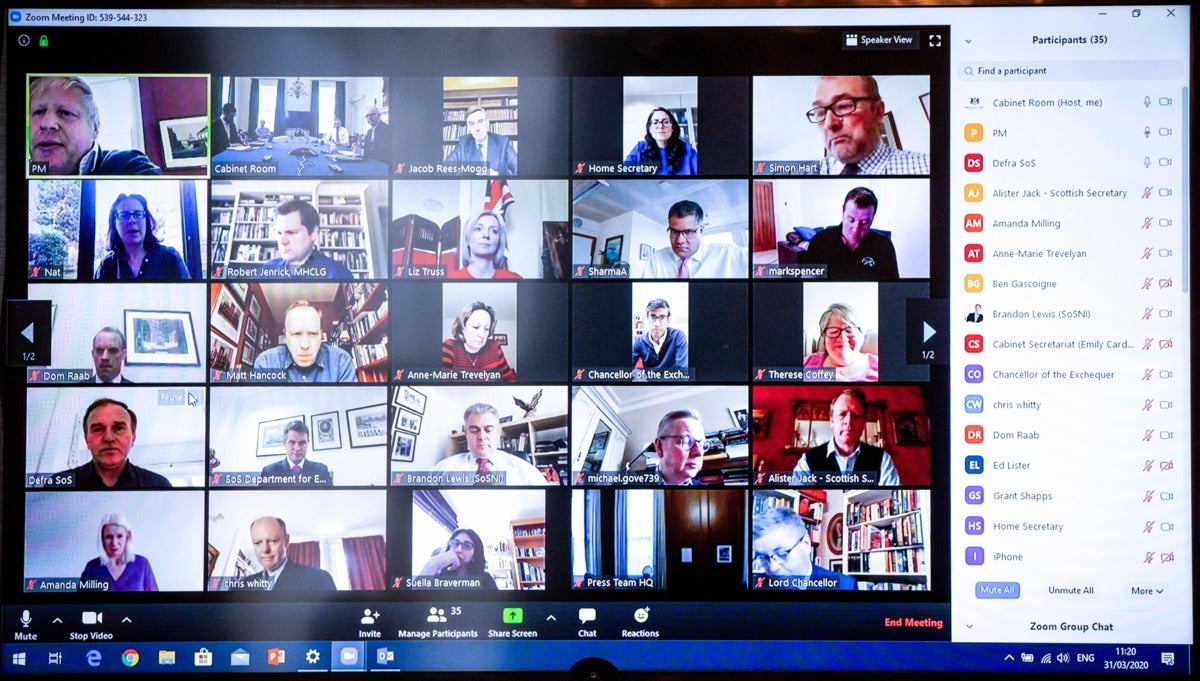

When work-from-home orders swept the globe in March, Yuan said his company would work to support those affected by the outbreak. As the app’s popularity grew, Zoom showed up in surprising places: it became, for instance, the platform of choice for the UK government. (British Prime Minister Boris Johnson made history by holding the first ever cabinet meeting via Zoom, though he was promptly chastized for posting a screenshot of the meeting on Twitter with the meeting ID clearly displayed.)

Boris Johnson / Twitter

Boris Johnson / Twitter British Prime Minister Boris Johnson held the first-ever cabinet meeting using Zoom; he wound up in trouble for inadvertently posting the meeting ID.

The secret to Zoom’s popularity lies in the platform’s ease of use. Setting up a Zoom call requires three things: a Zoom account, a webcam and access to the internet. Zoom encourages users to download the desktop app, although calls can be accessed via a browser with limited in-call features. Mobile users need to download the mobile version on their phone to participate in a call. The platform is compatible with Windows, Mac, Linux, iOS, and Android.

How to use Zoom

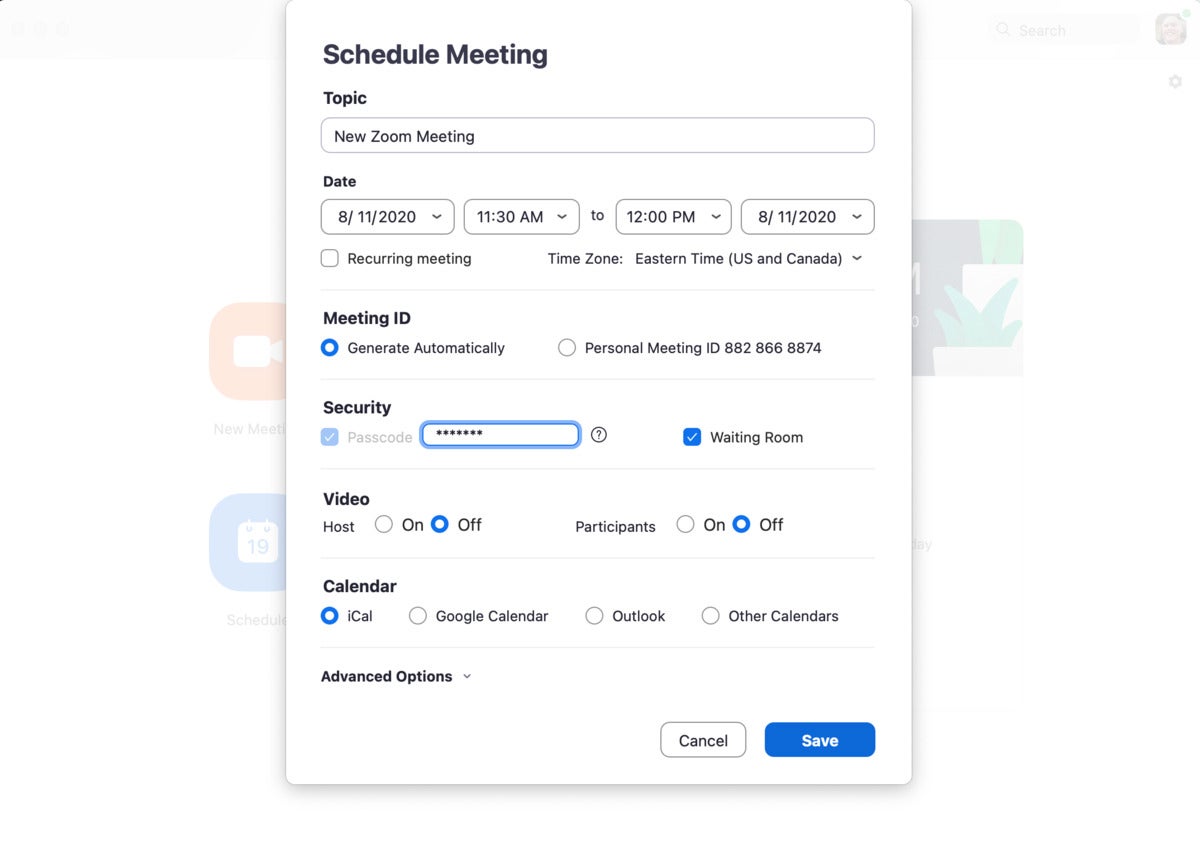

To initiate a meeting right away, you log on to the Zoom.com website, select “Host a meeting” — you’re given the choice to start with video on or off — and away you go. You can also schedule a future meeting using a form where you fill in basic details — enable cameras to be on or off, enable the meeting to be recorded, or set up a waiting room, among other options. Once you’ve scheduled the meeting, you can then share it via your Google, Outlook or Yahoo calendar, input the participants’ email addresses and send an email invite to them.

Zoom

ZoomZoom has taken steps to make meeting scheduling easier.

The maximum number of participants on a call ranges from 100 to 1,000, depending on whether you’re using the free or paid version of Zoom. (The free version also limits meetings to 40 minutes.)

What in-meeting features does Zoom offer?

Although Zoom prides itself on offering a high-quality meeting platform, the company treads a fine line between adding new features and not overwhelming it with the whims of every end user.

“Usability trumps features,” Zoom Chief Product Officer Nitasha Walia said at a 2019 PagerDuty event. “If users can’t use it how it’s intended, it doesn’t matter what features you have — people won’t be there to try them.”

The in-meeting features offered by Zoom are designed to be easy to find, easy to use and work as expected. Hosts are given the ability to mute and unmute participants, turn off screen sharing for attendees, make other people joint hosts and rename people once they have dialed in. Zoom also gives users the option to share individual desktop windows rather than an all-encompassing screen share, which is preferable for privacy.

For non-hosts, Zoom offers a plethora of in-meeting participation tools, including a whiteboard; a chat window where you can send messages to the group or individual attendees; a “raise hand” option that lets the host know if one of the muted participants has a question or a comment; and reactions so meeting attendees can silently comment via one of two basic emojis.

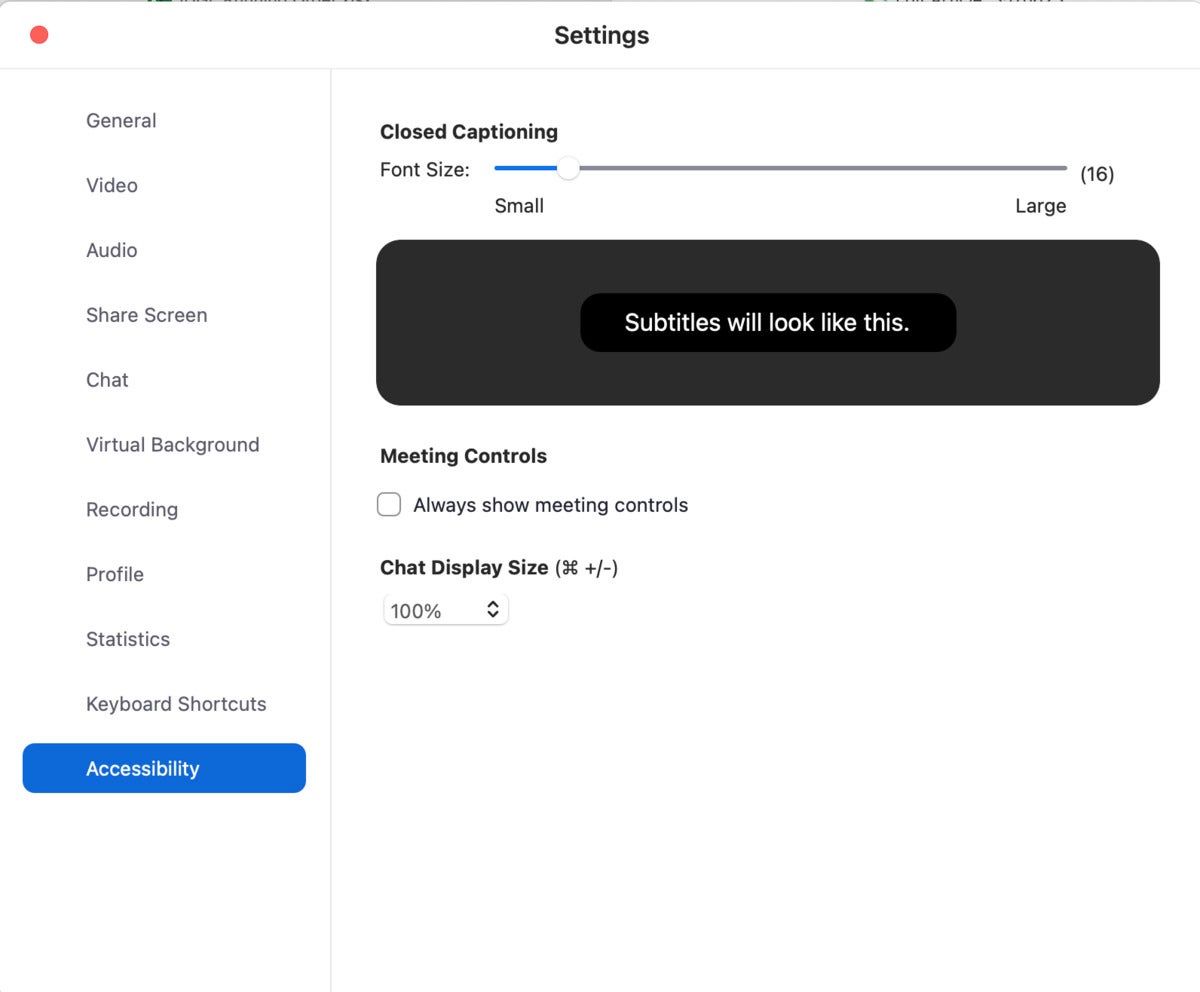

Zoom

ZoomZoom allows closed captioning.

For self-conscious users, there’s a “Touch Up My Appearance” option, which promises to “smooth out the skin tone on your face, to present a more polished looking appearance.” And if your device has the right graphics hardware, you can set up a custom background image.

Zoom has been working in recent months to bolster third-party integrations. Users of Otter.ai for Teams and Zoom Pro, for instance, have access to Live Video Meeting Notes, which provides meeting participants with live and post-meeting transcripts; users can highlight, comment on and add pictures to the notes via the Otter.ai web or mobile app.

How has Zoom addressed security concerns?

Zoom’s popularity explosion in early 2020 exposed a number of security and privacy issues that the company had not addressed as it grew. As the number of Zoom meetings skyrocketed world-wide, security and privacy experts took a closer look at the platform.

One of the first issues raised involved Zoom’s promise to offer “end-to-end encryption” of video chats. When that feature was called into question, the company had to clarify that Zoom had a different definition of “end-to-end” and “endpoint” encryption that fell short of common expectations.

Security gaps also led to “Zoom-bombing,“ where uninvited participants could gain access to a meeting if they knew the meeting number. Other problems included the inadvertent leaking of email addresses and profile pictures; sharing of personal information with advertisers; a 2019 bug in the Zoom Mac app that allowed malicious websites to silently activate users’ webcams and left a localhost web server behind — even after the app had been uninstalled; and a recently discovered bug that let hackers steal Windows passwords.

Notably, some of those security issues arose because new users did not understand how to configure the Zoom app to protect meetings. Analysts and security experts argued that security settings should have been enabled by default, especially for a platform that made its name on ease of use.

Because of the early spate of problems, a number of high-profile companies including SpaceX, Standard Chartered and the governments of Germany, Taiwan and Singapore banned employees from using Zoom.

In response, Yuan on April 1 announced the company would cease work on all new features for 90 days to address the burgeoning privacy and security issues. He acknowledged the company had fallen short of customer expectations, but argued the pandemic had brought in a crush of users “utilizing our product in a myriad of unexpected ways, presenting us with challenges we did not anticipate when the platform was conceived.”

Also in response, Zoom released Zoom 5.0 later the same month, adding support for AES 256-bit GCM encryption and dialing up protection for meeting data and resistance to tampering. The new level of encryption is available across Zoom Meeting, Zoom Video Webinar, and Zoom Phone. In May, the company said it had acquired Keybase, a secure messaging and file-sharing platform. Yuan called the purchase a key step toward building a “truly private video communications platform that can scale to hundreds of millions of participants, while also having the flexibility to support Zoom’s wide variety of uses.”

Despite the growing pains, Zoom’s efforts to make changes appeared to mollify critics.

“When faced with questions over security and privacy, Zoom reacted quickly and very publicly to the challenges, including their CEO holding weekly public security briefings,” said Wayne Kurtzman, IDC Research Director for Social, Communities and Collaboration. “Zoom was also quick to take actions on changing the defaults that helped address meeting privacy concerns, as well as setting a 90-day plan for deeper actions, and communicating it publicly.”

How is Zoom priced?

Zoom offers a range of different plans, which vary in terms of costs and the number of participants who can take part on a video call.

The platform’s basic plan is free and allows up to 100 users per call. (At the start of the pandemic, Zoom waived the 40-minute call limit for users of its free plan. That time limit is now back in place.) Although there are workarounds, there is also nothing to stop meeting participants from ending one video call and jumping straight onto another 40-minute one.

Zoom’s Pro plan costs $15/host/month and allows up to 100 users per call. However, unlike the free plan, once you start hosting your video calls via a paid plan, there is no time limit. The Business plan costs $20/host/month, requires a minimum of 10 hosts and allows up to 300 users per call. The Enterprise plan also costs $20/host/month, but requires a minimum of 100 hosts. The Enterprise plan allows for up to 500 users per call, or 1,000 with an upgrade to Enterprise Plus.

Zoom

ZoomZoom pricing varies by number of participants.

How does Zoom compare to its rivals?

The videoconferencing landscape is not short of vendors, with companies such as Cisco, Google, Microsoft and Facebook all offering enterprise users a video platform.

As a video-only platform, Zoom’s biggest competitors are LogMeIn’s GoToMeeting and Cisco Webex, both long-standing staples of the videoconferencing market. (In a comparative review earlier this year, Computerworld found Zoom’s video and audio quality, ease of use and overall user experience were better than the other two offerings.) For enterprise use, the introduction of end-to-end encryption in Zoom 5.0 positioned it ahead of some rivals, although Webex offered end-to-end encryption long before Zoom announced its rollout.

Throughout the pandemic, Zoom’s biggest rival has been Microsoft Teams — Microsoft’s all-encompassing collaboration platform that centers around group messaging and shared workspaces while providing users the option to video chat.

Launched in 2017, Teams has now largely replaced Skype for Business as the communications hub for the Office 365 and Microsoft 365 suites. Like Zoom, its popularity has grown significantly in recent months; the company in April said the platform has more than 75 million daily active users. And Microsoft has worked to improve its platform and address issues users flagged at the start of the pandemic. One change now allows users to see up to 49 people on a Teams video call; another creates virtual viewing modes that mimic in-person gatherings.

Microsoft

MicrosoftTogether Mode in Microsoft Teams puts video meeting participants in a virtual setting designed to make meetngs more engaging.

Because it’s part of Microsoft’s suite of office-worthy apps, Teams already has a toe-hold in companies that either didn’t have a collaboration platform in place already or are looking to limit application sprawl. And it’s worked to help IT admins better manage Teams video chats, again with an eye on enterprise users.

What comes next for Zoom?

Zoom appears poised to continue its growth, because even after the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, large numbers of workers are likely to continue to work remotely. While the company’s Zoom for Home announcement was not enthusiastically received, Kurtzman said it was still a smart move to position Zoom as a rival to other, more traditional UCaaS (Unified Communications-as-a-Service) vendors, which often offer hardware as well as software.

Kurtzman believes that, with most security concerns addressed, Zoom can now refocus on improving the video call experience for users. He pointed to the company’s recent addition of AR features, as an example.

“As a result of the pandemic, we are in a period of great public adoption and feature velocity in videoconferencing,” he said. “In the short term, Zoom wants to make meetings more engaging and less stressful, which explains the AR features added recently. Zoom wants to connect with more enterprise systems to remove friction between meetings and work. They already support a rich API set that easily integrates with a number of applications.

“Long term, despite the fierce competition, their vision is to reinvent how we use videoconferencing both as enterprises and personally,” Kurtzman said.

In doing so, it’s important that Zoom balance the need to be both feature rich and easy to use, not making the user interface more complex than it needs to be.

“Zoom has clearly taken advantage of the moment,” Kurtzman said, noting that the company was quick to address security issues as they arose — offering end-to-end encryption is the exception, not the norm, for videoconferencing platforms. That should keep it in the top tier of players in the market.

“Unlike previous years, the growth of collaborative applications — including conferencing — enabled multiple market leaders,” Kurtzman said. “Zoom is well-positioned for such a position.”

Copyright © 2020 IDG Communications, Inc.